Losing Oneself in New York

John Haberin New York City

Alvaro Urbano and Scott Burton

Paul Rudolph, Brutalism, and Architecture

To live in an ever-changing city is to know loss. It is what makes you a New Yorker—the passing of friends and loved ones, the restaurant where you knew the menu by heart, the bar where customers knew you by name, the bookstore that taught you what and how to read. For Alvaro Urbano, it is as if a painting had come to life, only to insist by the very stillness of its actors that he will never see them again.

The show is his "Tableau Vivant" (literally a living painting) at SculptureCenter. Successive "In Practice" projects take the back room. Urbano pays tribute to a place where people once gathered and to its one-time creator, Scott Burton. Alvaro knows that he cannot bring back either one.  You can still see benches from Burton in Manhattan, and people really do gather there and take their rest, but you better hurry. A renovation in Battery Park City has already slated them for removal.

You can still see benches from Burton in Manhattan, and people really do gather there and take their rest, but you better hurry. A renovation in Battery Park City has already slated them for removal.

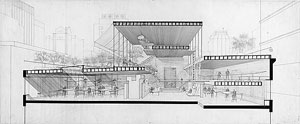

What do you personally hate most about modern architecture? The odds are good that Paul Rudolph will have had a hand in it. Could that be why his star has faded, to the point that you may never have heard of him? The Met places him at the very heart of his generation. It asks to see his work as soaring into space in all its material form. True, if his most ambitious plans for New York had come to be, the Lower East Side would never have become a gallery scene, but gentrification has closed more than a few hot galleries anyway.

But seriously, what is it about modern architecture that drives you crazy? Is it Brutalism, with its concrete façades and, at times, brutal assault on the viewer? Rudolph called concrete "the material that can be anything." Is it the urban planning of Robert Moses, leveling and dividing entire neighborhoods, with highways that still cut off half the Bronx from the other half and Flushing Meadow Park from the largely Dominican community. Rudolph was there, too, as designer of highways that would have barreled through Washington Square Park and the life of lower Manhattan. If Moses has become the evil mastermind in stories of New York, surely Rudolph deserves a terrible place at his side.

Is it the isolation of apartment towers for the wealthy few? Is it their long shadow cast on Central Park and capitals of Asia? Rudolph found commissions across Asia, for skyscrapers that left landscaping, public access, and pedestrian traffic to others, should they care. Yet he never lost his love of open space and modern materials. The fine shading of his pencil sketches alone aligns his interiors with sunlight. At his death in 1997 he still sought his "concretopia."

Minimalism in spirit

Not that it matters, but a tableau vivant was a nineteenth-century fashion, and it, too, is not coming back any time soon. People put on an act, staging a favorite work of art. No worse, I suppose, than those who use 3D glasses and projections to put you in the middle of a painting, as if The Starry Night were a planetarium—and no better. Alvaro Urbano's tableau, however, is no mere reproduction. He salvaged whatever he could from the atrium at the former Equitable building in Manhattan, only a block from the Museum of Modern Art. That does not include people.

Back in the 1980s, Scott Burton brought Brutalism to Minimalism, as if nothing could be more hostile to human feeling, but with fine marble and flowers. He had an architect's sensibility as well—a commitment to public spaces. Not all were cherished, and not all survive, but such is the city. This one fell victim to yet another tasteless renovation in 2020. Born in Madrid and based in Berlin, Urbano got there just in time and carted off roughly half. The result steals the show, as Atrium Furnishment.

Presence and absence alike haunt its semblance of a plaza where people once hurried past or stopped for lunch. It is a recreation in spirit, and spirits can be threatening. Urbano breaks up Burton's marble circle, meant to evoke a clock face and the dreaded nine to five. It can now broaden to cover SculptureCenter's main hall. (Converted by Maya Lin, the former trolley repair shop has its own spirit life.) It has the original's beauty, but also its formidable mass, and it no longer welcomes seating.

Visitors are warned not to touch, for their own sake as much as the work's. Leaves that have seemingly fallen are metal, with sharp edges. Their fall colors bring a reminder of death. Much the same colors shine out from light boxes propped here and there on the marble, streaked like a rock face and a geological record. The original's flooring is gone, but a drop ceiling has collected no end of dust, and one lone object bangs against its glass as if trapped within.

Bastien Gachet has his own "object-based dramaturgy," as he calls it, in the side room (since given over to Tony Chrenka). Where you might hope for a bathroom, he sets a bone-dry sink. A keyboard lying on top has nothing to communicate, and a bucket on the floor holds what could be diluted blood. The rest of the installation lacks quite the same shock, but its bare wood furniture is creepy enough. I cannot swear what it has to say, least of all something about "pre-intentional," real, and fake. It seems real enough to me.

Still, he and the more evocative work out front should have anyone asking what has been lost. Gachet also speaks of the imminent, emergent, and durational, and Urbano, too, confronts the passage of time. Burton's trees have become his bare leaves, which can never die because they were never alive. They also create a bridge from the chill of an office building to the fragile warmth of Central Park. He took the form of his leaves from the Ramble, north of the park's lake and south of the Delacorte Theater and Great Lawn, once a popular queer pick-up space. Burton died of AIDS in 1989.

Hating architecture

To tell the story of modern architecture through the eyes of Paul Rudolph is like retelling Othello from the point of view of Iago, but with a difference. In place of that arch-villain's "motiveless malignancy," Rudolph laid out his motives clear as can be, and they can seem downright contemporary. In fact, he may have a closer parallel in Othello himself, with a spectacular rise and fall. He became chair of Yale's School of Art and Architecture in 1958—and proposed a new building for it four years later. His plans for Robert Moses put him on magazine covers. That includes plans for yet another highway, along the Hudson River waterfront—all too close to where the city's wealthiest galleries stand today.

Their failure made the magazines, too. The argument, by Jane Jacobs and others, against his assault on the street grid has been central to visions of the city ever since. Had his plans for the waterfront gone through, miles of parks, sculpture by David Hammons, the High Line, and Little Island would never have come to pass. Sometimes the good guys win one, and this time they did. Washington Square Park has had a revival. Just how bad, though, were the bad guys?

Their failure made the magazines, too. The argument, by Jane Jacobs and others, against his assault on the street grid has been central to visions of the city ever since. Had his plans for the waterfront gone through, miles of parks, sculpture by David Hammons, the High Line, and Little Island would never have come to pass. Sometimes the good guys win one, and this time they did. Washington Square Park has had a revival. Just how bad, though, were the bad guys?

Unlike Moses, Rudolph was not content with subordinating neighborhoods to suburban access. He imagined integrating highways and vital architecture in a single structure, with towers overlapping roads. In his sketches, you might have trouble spotting the cars. Nor was he averse to decoration in architecture, although he preferred to find variety in the materials themselves. He saved a panel by Louis Sullivan in the shape of an older carving—perhaps because its plaster reminded him of the potential of concrete. Colored pencil enlivens his design for a chapel, to the point that rising diagonals of color overpower the worshippers and the altar.

The curator, Abraham Thomas, places him in the "second generation" of modern architecture, along with I. M. Pei and Eero Saarinen. Pei's entry pyramid for the Louvre has a place in public memory, so why not Rudolph? Saarinen's TWA Terminal at Kennedy Airport has become a hotel precisely because people will not let it go. The Met does not so much as mention such older architects as Marcel Breuer, whose former Whitney Museum made Brutalism itself a marvel. Nor does he mention Louis I. Kahn, whose Yale museums upstaged Rudolph's academic towers and showed that concrete, too, can admit the light. Rudolph has no such fans, but he can help see what connects them all.

Consider how he went about constructing a tower. He worked like a child playing with blocks, stacking and staggering, to the point that the supporting elements in the glass of his midtown Modulightor building become enlivening accents. It brings rhythms and variety—and encourages the eye to rise along with it. It cab amount to repeated cantilevers, as with Frank Lloyd Wright, but without asking to defy gravity. It is modular, making it adaptable and affordable. Air and light can enter freely as well. Most of all, it calls attention to Rudolph's favorite materials.

So what if they land like a ton of bricks? His designs keep rising, but do human beings have a place? His tubular wheeled chairs recall the Bauhaus, but are rigid and uncomfortable all the same. Still he was fully a part of his time. When he allows near cylinders to run the length of a structure, he approaches Kahn's translucent Kimball Museum in Fort Worth. His own firm, near the Plaza Hotel and since demolished, anticipates today's fondness for open offices. You can decide whether they would be open to you.

Alvaro Urbano ran at SculptureCenter through March 24, 2025, Bastien Gachet through October 21, 2024. Paul Rudolph ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through March 16, 2025.