Beneath the Stars

John Haberin New York City

Vincent van Gogh: Cypresses

Into the Woods: The Cohen Gift to the Morgan

What is it about Starry Night? What do you remember?

Of course, it is night, the town shrouded in darkness but touched by the brilliance of the sky. Of course, too, it is starry, and these are no ordinary stars. Vincent van Gogh permits few streaks of true black, most of those on distant hills, and nothing at all like constellations. The stars have swollen to compete with the uncanny yellow of the moon amid circles of white.  They swirl in a concerted, tempestuous rhythm, with sky, clouds, and everything below caught up in it. Who can number the shades of yellow, black, blue, and white?

They swirl in a concerted, tempestuous rhythm, with sky, clouds, and everything below caught up in it. Who can number the shades of yellow, black, blue, and white?

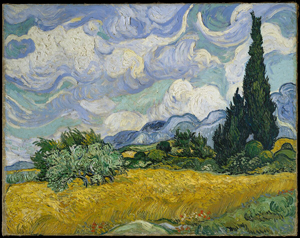

Did you also notice the painting's single largest element? Did you notice the cypresses? Maybe not, but the Met will not let you forgot. It uses them as a guide to two years in the south of France, nearing the end of his career and his life. Just forty works are enough to stop you in your tracks, as the trees once did for van Gogh. They are enough, too, to ask how he turned to nature for both spirituality and observation—and what he received in return.

As almost a prequel to van Gogh, the Morgan Library returns to one of art's most enduring mysteries: however do you get from Romanticism to realism, Impressionism, and a thoroughly modern future? But you already know: it took a trip "Into the Woods." A show of that name pays its dues to a gift from Karen B. Cohen, with the usual suspects and some surprising answers. It has not just French drawings but also photographs and, at its center, a novelist, George Sand.

The road to Saint-Rémy

Not everyone has a proper chance to see van Gogh's cypresses, because not everyone has a proper chance to see Starry Night. Visitors to MoMA gather reliably in front of it, blocking the view, to the point that a half-empty museum after Covid-19 came as a relief. At the Met now, too, the painting draws the most attention, at the show's physical and chronological center. Starting in April 1888, the artist got to know Arles, checked himself twice into a mental hospital in Saint-Rémy, and found a comfortable studio on his final release. The show's three rooms take each move in turn, ending before he left for Auvers-sur-Oise outside Paris—and, in 1890, his death, almost certainly by his own hand.

He must have felt isolated, away from his haunts and his peers, but he wanted it that way. He could still write to his brother, Theo, an art dealer and his greatest supporter, to share his impressions, but that is about it. He was no longer in the daily company of Paul Gauguin, although Gauguin visited him in Arles. He was essentially his own companion, and people in his work appear small and distant. He was tired, though, of the big city, the competition, and the failures. And he looked for renewal to the countryside and sky.

For at least a moment, he must have felt that he had found it. He singles out native trees, like willows, poplars, and (yes) cypresses. He incorporates orchards and flowers as beds of variegated color, in short parallel verticals. Their borders and surrounding roads lend structure. If their artifice were not enough, he satisfied his taste for Japanese art in a bridge at Arles. A woman crossing carries a parasol to suit the style and occasion.

He must have found hope, too, in his studio in Saint-Rémy, in Provence. Sunlight and space to work were to make a huge difference to Henri Matisse, too, when he moved to the outskirts of Paris in years to come. Gogh could count on a fine window, clean bottles and jars on the sill, and his own art on the walls. He gets out more as well—and not just at night. Paintings take more care for the course of a day, with softer gradations for twilight and the deep red of a setting sun, burying itself in the hills and setting them in motion. These are moments of transition, and happiness for him was transitory as well. An olive grove has a warm brown that he could otherwise not allow.

He seems more at home as well with the people around him. He can almost share in their lives, their feelings, and a twilit walk, although they are couples, and he is apart and alone. It is striking, too, how little they labor. Were van Gogh's boots in paintings from 1886 a working man's or his own? Painters like Jean-François Millet and Camille Pissarro had celebrated the peasantry not all that long before. Yet the small, often faceless figures pass through without a hint of the existential dignity of work, a closeness to the earth, or the weight of the world.

He seems more at home as well with the people around him. He can almost share in their lives, their feelings, and a twilit walk, although they are couples, and he is apart and alone. It is striking, too, how little they labor. Were van Gogh's boots in paintings from 1886 a working man's or his own? Painters like Jean-François Millet and Camille Pissarro had celebrated the peasantry not all that long before. Yet the small, often faceless figures pass through without a hint of the existential dignity of work, a closeness to the earth, or the weight of the world.

And then there were the months in between, the months of anguish and taking a knife to his ear. van Gogh was never fully at ease, and his appreciation of nature's rhythms only adds to the inner tension. Still, he liked it in the hospital, and checking himself in gave him the freedom to venture out to continue work. Did you know that he painted Starry Night, in June 1889, from a window in his room? He liked the hospital garden, too, with a cypress tree right there beside its steps. And that brings the story back to the painting and the trees.

Still point in a changing world

He saw cypresses from the first, and he saw them everywhere. They have a modest place behind a garden, but a defining one, multiplying along the horizon. You may not notice them here either, but a pair appears to the left of that drawbridge in Arles, echoing its twin towers and the paired wires that opened it to river traffic. They echo the trees of an orchard as well, like its dark companion. Most often, in fact, they appear as a pair, diverge from one, or merge into one. So much of humanity passes in lone pairs, too.

They could be the dark underside of nature and humanity or their guardians. Cypresses swell like teardrops at their base, like the swirling clouds, moon, and stars. They taper as they ascend, pointing to the sky. They parallel the church steeple of Starry Night, but as a far taller and more formidable presence. Their deep greens penetrated by brown could be the one still point in a changing world or a barrier to entry. They might be the dark underside or the point of stability in van Gogh's mind as well.

He might have sought them out had they not come to him. "I need a starry night with cypresses," he wrote Theo, "or perhaps above a field of ripe wheat," and he got both. The curator, Susan Alyson Stein, calls Wheat Field with Cypresses, also from June 1889, the starry night's "daytime companion." And it, too, has its swirls, only in the calmer light of day. Together, the two paintings suggest the region's characteristic life forms and productivity. They also suggest the tortured ambivalence in van Gogh's mind.

The Met highlights the cypresses but shies away from the ambivalence. It never once mentions Gauguin or suicide. By its very subject, it cannot include a self-portrait with bandaged ear or a portrait of one who treated him, Dr. Gachet. It treats the hospital only as a figurative window onto the starry night and a literal asylum, a refuge. One might think that van Gogh left Provence to embark on a whole new life. Yet the show's last paintings are all from sleepless nights, and the town in Starry Night might be in a collective nightmare.

In singling out the wheat field, from its collection, the museum could be celebrating itself. Could that be the point of the exhibition? As always, one should take anything the Met does with a grain of salt (and that includes its show this past year of Cubism as trompe l'oeil). It has the authority to let its theses and its holdings rule. In fact, van Gogh painted several versions of the wheat field, over months. And the farmhouse that might have cultivated it has tumbled into the trees.

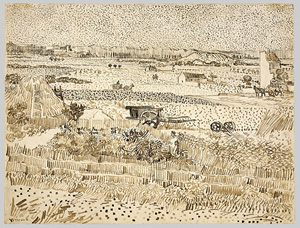

Still, it offers a rare look at late van Gogh, in all its power and complexity. It includes the skill and complexity of his technique as well. His letters contain sketches flowing from a reed pen. Other van Gogh drawings paper have an amazing finish, with dense stippling, even as studies for painting. Oils transform the detailed color changes of Claude Monet and Impressionism into true impressions of nature, as impressions on him. They throw the distinction between observation and symbolism to the winds.

Why leave Paris?

I have, I confess, never read a novel by Sand, but she was once more popular than writers I know well, from Stendahl to Balzac, Zola, and Flaubert—and from Romantic illusions to urban realism and formal experiment. She also had an affair with Frédéric Chopin, mingled with such painters as Théodore Rousseau, and sat for a photo by Félix Nadar. She tried her hand, too, at watercolor and gouache, and the Morgan has nine examples from around 1875. They are credible at that, with clear colors and easy leaps into distance. She was, in short, interdisciplinary (not to mention gender bending), and so for the Cohen gift was art. It looks to early photography as a clue to drawings.

It starts, though, with drawings and more familiar answers. Artists like Jules Breton and Millet idealized peasant labor, and what more could it take to compel them to leave Paris for simpler truths? It taught them the very basis of Romanticism, the dual priority of fact and feelings—and the interconnection between the two. Increasingly, too, they found that interconnection in landscape itself. Théodore Géricault exchanged his epics for a horse-drawn cart and wind-swept trees. Soon those connections brought Camille Corot back to the city and suburbs, for a new visual language.

They valued landscape artists before them, from the great age of Dutch painting. The show has room along with the French for Rembrandt and Jacob van Ruisdael. Yet one can see the difference, in just how much artists infused landscape with feeling.  With Rousseau, Rembrandt's modest cottages become a village in sunset and a shelter nestled in the trees. With Corot, Ruisdael's sun-dappled trees broaden even as they reach for the sky. van Gogh's cypresses are on their way.

With Rousseau, Rembrandt's modest cottages become a village in sunset and a shelter nestled in the trees. With Corot, Ruisdael's sun-dappled trees broaden even as they reach for the sky. van Gogh's cypresses are on their way.

The interconnections also lead to explorations between day and night, culture and nature, objects and light. Moonlight pierces the trees for Paul Huet, much as foamy waters create a center of light for Rousseau. Could, though, photography have changed what they saw? Its long exposures and brushed glass plates enriched many a landscape, much as Corot found a darker, more even texture in moonlit trees. Photography, the Morgan suggests, also enforced a single point of view, even in panoramas. Perspective would never be the same again.

Much early photography is posed and theatrical, and photographers took their cues from painting. For the Morgan, though, it brought a new attention to fact. Peasant labor becomes subordinate to the object of labor, much as Karl Bodmer documents charcoal burners. An unknown photographer cuts off the head of a shepherd to focus on his sheep. Albert Lebourg changes the subject entirely, from women in the kitchen to pots gleaming on the wall. Could François Bonvin have seen something like that when he sketched a candlestick looking like heavy equipment?

I have my doubts, but the Morgan has one last answer to why artists went into the woods—because they could. Railroads brought them first to Fontainebleau and then to Barbizon, just in time for Pre-Impressionism (and, later for Pablo Picasso). They found the marks of industry there as well, in valve works and aqueducts. Charles-François Daubigny sketched one of the new train stations in Paris, with a majestic steel frame supporting its glass roof. It allowed a thriving middle class its day trips up the Seine, along with Georges Seurat and Claude Monet. That change, though, was still to come.

Vincent van Gogh's "Cypresses" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through August 27, 2023, the Karen B. Cohen gift at The Morgan Library through October 22. Related reviews look at van Gogh drawings, the van Gogh Museum, his portrait of Dr. Gachet, and Romantic landscapes.