Stone and Sky

John Haberin New York City

Louis I. Kahn: FDR Four Freedoms Park

Yale University Art Gallery

Louis I. Kahn's FDR Four Freedoms Park makes more than one lasting impression. On leaving, you may still be torn between them.

There is the park as architecture, with that first impression of massed white stone, hard edges, and high stairs. There is the park as landscape, in the southern tip of New York's Roosevelt Island open to the river and the city. And then you may chance to look up as you exit, and the two may almost become one: the stairs led all along to the sky. In fact, the architect's last completed building, the Yale Center for British Art, poses the two from the very first. Discovering them again helped me come to terms with real doubts about an impressive career.

I ducked inside at Yale for a refresher course, for I was in New Haven to see the Yale University Art Gallery across the street. A reinstallation fully opened on in December 2012, after a decade of renovation. Duncan Hazard and Richard Olcott of Ennead Architects (formerly Polshek Partnership) finished work on Kahn's addition to the building in 2006. That 1953 building now serves as the sole entrance, with a broad lobby, a small sculpture garden out back, a single large room for temporary exhibitions to one side, and galleries above. Now, too, the museum runs beyond both these and the Old Yale Art Gallery, from 1928, and into Street Hall—from 1866 and every bit one's image of an Ivy League university. I wanted to see how it all comes together, but I needed another look, too, at Louis I. Kahn.

Freedom of the Parks

What if the funding just came in to complete the pyramids? Would the result still look glorious—or a dated and ominous enigma? Would it belong to a past civilization or to this one? In March 2010, construction of FDR Four Freedoms Park began at last, thirty-six years after the architect's death, and the park opened in November 2012, after a brief, unplanned delay for Hurricane Sandy. And its thousand tons of Mount Airy granite really do have something of the pyramids in their splendor and weight. One has, both physically and mentality, to get past at least some of it to think of freedoms in the present.

The park's four acres pay tribute to Franklin D. Roosevelt's four freedoms, the core of his 1941 State of the Union message—freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear, here and "everywhere in the world." In another collision between past and present, they also pay a kind of tribute to Kahn, the architect, and to John Lindsay, the mayor who proposed the park. They complete the southern tip of Roosevelt Island and, in the process, help to open the island and to shift its balance. Those who take the overhead tram or subway have looked mostly north, to housing and to the gothic lighthouse at its tip (by James Renwick, Jr., the architect of Grace Church and Saint Patrick's Cathedral), just across from Socrates Sculpture Park and the Socrates Annual in Queens. When Lindsay and Governor Nelson Rockefeller announced plans for the park and renamed the island for Roosevelt, in 1973, none of that was there but the lighthouse (although the master plan, by Philip Johnson and John Burgee, dates to 1969). But "America's mayor" lost office, Kahn died the next year, New York City approached bankruptcy, the streets grew darker at night, and thoughts of a park were gone.

Even now, at least until Cornell University builds its engineering school here, one is likely to remember the island, mistakenly, as ending just south of the 59th Street Bridge and the tennis center. Beyond that? A hospital and ruins, including the ruins of a smallpox hospital. To reach Kahn's legacy, one has a fifteen-minute walk past them, which makes his Modernism all the more distant and imposing. One must first cross South Park, through a barely visible door in one fence, around a high mound of shrubbery above a low stone wall—before reaching yet another gate, closed Mondays through Wednesdays and at six, at least for now. Apparently the four freedoms do not include freedom of access to public parks.

Those who make it in find white granite to either side, somewhere between thick walls and hard benches, with twenty-four broad steps between them, hiding everything but the sky. They could belong to a pyramid that never came to completion, albeit the Mayan kind—and their sloped sides look all the more dismal and sunken from across the water, like a bunker. So much has changed in the construction of a memorial since Kahn's day, thanks in no small part to Maya Lin and to Minimalism. Where her Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington or, more recently, the National September 11 Memorial in New York sinks into the earth, this site rises upward, in all its one-hundred forty thousand cubic feet of North Carolina rock. One has a choice of following the horizontal along the waterfront or taking the stairs. Either way, one reaches at last a true park.

The surprise is the openness, of the tapering grass between two rows of lindens and the water, in what should never have remained "never built New York." Beyond lie the East River leading to the ocean, Lower Manhattan with Roosevelt's dream of a United Nations, and Long Island City with its high rises behind the older and more comforting Pepsi Cola sign in Gantry State Park. The architect imagined the park's triangle as a barge or the prow of a boat, and one could be sailing into the light. I should have known, from the Kimbell Art Museum or the Yale Center for British Art, how for Kahn geometry, space, and light go together. But then one encounters his imposing granite niche, with the text of the four freedoms (in full capitals) and Jo Davidson's gigantic portrait head of Roosevelt, modeled in 1933—before turning back to a vista of the smallpox hospital and a long walk home. And that experience, flawed but memorable, says something about the tensions within Modernism, both esthetic and political, or between Modernism and today.

Soon after Welfare Island became Roosevelt Island, long after an asylum and a penitentiary had moved elsewhere, welfare itself became a dirty word. When Roosevelt calls for four freedoms, for "jobs for those who can work," for "equality of opportunity," and to "widen the opportunities for health care," he sounds radical now, but he included them with the need for airplanes and munitions. Less than a year before Pearl Harbor, he saw them as equal parts of opposition to "the so-called 'new order' of tyranny." For him, "That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation." Maybe not, but the park took two generations all by itself.

A museum loop the loop

Kahn's contribution to the Yale University Art Gallery long before is now all the more a part of an abundant whole. Upstairs, one is unlikely to spot where it ends and the old galleries begin. The renovation is above all a restoration, a stunning contrast to MoMA's planned destruction of the former Museum of American Folk Art, and the operative word is smooth. Small additions, like radiators and grillwork, pick up on older designs. Most choices came about as collaborations between the architects and curators, who managed to keep much of the museum open all along. One can see that clearly in the American wing, in Street Hall, where paintings get the rooms one floor above decorative arts and period rooms, to benefit from the skylight.

Smoothness here means circulation, such that one can loop back and forth along four floors, using the stairs at either end. One becomes most aware of the renovation in a central glass elevator and the passage to Street Hall, across High Street. Claiming that building meant relocating the art history department, as part of a serious expansion, including construction into a former skylight. A fifth floor, which does not reach to the oldest building, now holds temporary exhibitions, works on paper, and access to a still higher study center—where professors can choose from the collections and direct their students. Other additions include a small balcony for sculpture and a separate gallery for Indo-Pacific art. The sole break in the loops comes on the main floor, with a gallery for early Christian and other art from an excavation in present-day Syria.

Smoothness here means circulation, such that one can loop back and forth along four floors, using the stairs at either end. One becomes most aware of the renovation in a central glass elevator and the passage to Street Hall, across High Street. Claiming that building meant relocating the art history department, as part of a serious expansion, including construction into a former skylight. A fifth floor, which does not reach to the oldest building, now holds temporary exhibitions, works on paper, and access to a still higher study center—where professors can choose from the collections and direct their students. Other additions include a small balcony for sculpture and a separate gallery for Indo-Pacific art. The sole break in the loops comes on the main floor, with a gallery for early Christian and other art from an excavation in present-day Syria.

With a grand opening, naturally the emphasis is on the museum's holdings. Both spaces for temporary exhibitions draw on the permanent collection, as does a small alcove in modern art for work by women. Kahn's windowed room has sculpture by Nam June Paik, Buckminster Fuller, and such contemporary names as Matthew Barney, Janine Antoni, and Rachel Harrison—in that trendy style of oversized odds and ends. The top floor surveys Societé Anonyme, an experiment in artist-directed exhibitions that feels right at home with DIY in Brooklyn now. Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Katherine Dreier took a space across from the central New York Public Library in 1920, for what grew to include Wassily Kandinsky, the enigmatic flatness of an interior by Charles Sheeler, and that killer Stuart Davis with Champion across the center. Duchamp's tumbling mural-scale Tu M' has a 3D element that I had forgotten (a wire brush), and Joseph Stella turns out to have painted much more than the Brooklyn Bridge.

Many of the same names appear in galleries for modern art, just one indication of the museum's depth. Arabesque by Jackson Pollock and three canvases by Mark Rothko put MoMA's near denial of its contributions to Abstract Expressionism to shame. I could start on other old acquaintances, but one can hardly review an entire museum. I had missed a Pontormo Madonna's eerie calm above a crying child, a Maine sunset by Frederic Edwin Church, a typically reserved still life by Giorgio Morandi, if not early Morandi, and a firmly three-dimensional Kurt Schwitters, but suppose I stop there before this review becomes a laundry list. Yale has particular strengths in late medieval and early Renaissance Italy—as well as a university's inevitable gaps, such as a paucity of modern sculpture and a bias in Asian art toward Japan. Still, this museum could compete for attention with any in America after the Met.

The loops impose some interesting and maybe loaded choices as well. This is not quite the march of history that you may expect from the Modern or the Met. Take the new spiral stairs from the lobby, and you come first to African and then Asian art. Take the central stairs or the glass elevator, and you land right in the middle of European painting. That runs all the way through Post-Impressionism, the movement that Félix Fénéon championed so well, so that Modernism hits you right away with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Museum fashions and egos being what they are today, the changes also include some new attributions to bigger names—a topic best left to another occasion, when the initial impact has worn off.

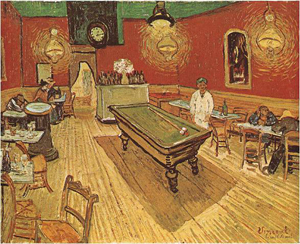

Again, though, the museum would be quite happy if you hardly noticed. It wants you to know how new all this is, after fourteen years of work, but it would also love you to think of its breadth all along. As part of its innovations, the loop circulates through period rooms, rather than making them dead ends. This places decorative arts more on a par with painting, as with the Gregory gift to the Frick, and it refuses to let you think that you are stepping into an altogether different world than your own. And as part of its conservatism, the walls for Western painting are anything but white, in the stately manner of many a British or European museum. A doorway frames the familiar sight of Vincent van Gogh and his Night Café, in case you were worried.

Brutalism without brutality

The impulse to both innovation and conservatism takes one back to Yale's history, in those three buildings and Louis I. Kahn. Maybe your first associations with Yale are a cheap ticket to Chelsea, with the prestige of its MFA program. Maybe you remember the Yale faculty for the stricter heritage of Josef Albers. (The modern rooms have more than one version of his Homage to the Square.) What about Kahn, though, who could work on such ambitious projects as India's national parliament, what does it say about his evolution over twenty years? One can contrast his two buildings less than a block apart.

Outside the Yale Center for British Art, the white, windows, and set-back corner entrance present a model of efficiency and welcome. Step inside, and the lobby looks more imposing. The gray concrete court rises with all its weight, and you may hesitate cross to the front desk. Besides, you may be too busy looking up into the air, pretty much the building's height. If you do dare to proceed, no one will blink, because all Yale's museums are free. If you make it to the fourth floor and another court, the play of rectangles makes the geometry clearer and livelier as well.

In between, you get the payoff—and it is, in every sense, both massive and light. The volume above the lobby becomes space, with the galleries on all four sides. As you circulate a great collection, you never lose sight of the exterior windows and interior atrium. They serve as a guide, and such favorites as John Constable and J. M. W. Turner (plus some noted Europeans and Americans who worked in England) feed on the openness. A gallery past the main rectangle runs two floors, picking up the initial impression of height and turning it to curatorial purposes. Throughout, wood frames and tempers the views onto the atrium, much as with the Phillips Exeter Academy Library, begun in 1965, giving more definition and more lightness.

In the Yale University Art Gallery, one may never once be conscious of the outside world, apart from the bridge over High Street. That represents a curatorial decision, in curtains and louvers to protect the art, but also a very different Kahn. Outside, narrow windows running the height of the building mark the entrance, surrounded by mass. Inside, coffered ceilings positively loom over the galleries with their gray concrete triangles. One can see more clearly his relationship to Brutalism, as in the intricate rectangles of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, begun in 1959. One remembers the Kimbell Art Museum in Forth Worth, Texas, begun in 1967, for the barrel vaults that bathe the art in diffuse light, but they are still concrete and travertine tunnels.

Then again, one can see the persistence of mass in Kahn's late work differently after the Yale University Art Gallery, and one can see ambiguity and innovation from the start, well before the age of "starchitects." The older museum's tall entrance windows anticipate his later play across several stories. The coffered ceilings allow flexible placement of lighting, as part of attention to such infrastructure details as air circulation. They also allow for his "floating walls," to adapt galleries to the art, although the ceilings themselves will never float away. He is already thinking about architecture as floating in one's field of vision. Kahn actually disliked Brutalism for its, well, brutalism, although he could not have known Scott Burton, and his museums share the campus with the Brutalism of Paul Rudolph and the 1958 Yale Art and Architecture Building—now the school of architecture, where Kahn first taught and remained until 1957.

Maybe few will come to the Yale University Art Gallery for the architecture. With its buildings spanning more than a block and more than one hundred years, one may have difficulty so much as finding the architecture. Too many museums these days choose between preservation, as with the Morgan Library and Drawing Center, or to big boxes that overwhelm the art, as with the New Museum and MoMA. This renovation all but avoids the question entirely, but maybe this way one is less like to blame the Yale Center for British Art (or British art itself) for museum atriums today more suited to grand hotels. This way, too, the building works, and I have so very much left to see. And then I can always cross the street or return to the East River to reach for the sky.

Louis I. Kahn's FDR Four Freedoms Park had its dedication ceremony on October 17, 2012, and opened October 24, but the public could not get in until November, after recovery from the storm. The complete renovation of the Yale University Art Gallery opened December 12.