Modernism Begins Again

John Haberin New York City

Early Film in Cubism

Henri Matisse Textiles and Stuart Davis Drawings

Modernism remade art from the ground up, or so the story goes. Why, then, are people so eager to explain it away?

Modern art built on years of collaborations and explorations in the half century before, and it reinvented the relationship between tradition, an artist's imagination, and representation. It has a rich context in clashing egos, politics, and culture of the twentieth-century. It also has a love-hate relationship with everything from fine art to photography to fashion. Why, then, do popular histories keep wanting to reduce it a mirror of life?

No, art's strangeness still has not gone away, and it still makes almost everyone at least a little uncomfortable. So, for that matter, do the last hundred years or so. They question the whole idea of fixed meanings and a point of origin. That can easily make one desperate for both—or at least an explanation. The problem arises once again with three shows about critical moments in modern art.

One finds the origins of Cubism in the movies, while another grounds Henri Matisse in the family business, textiles. Carrying the story to America, Stuart Davis gets to speak for himself and his own relationship to high and low culture, in his drawings and notebooks. All but the last miss the point, but all give a fascinating look at key creators. They also force one to revisit the supposed purity of modern art.

Cubism in motion

"Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism" opens with a stunning image. Of course, it unfolds on-screen. A dancer all but floats across the room—or is it dancers? All one sees is billowing color. The pageant fills the center of a darkened gallery with bright lights, swirling fabric, and the music of a carnival.

Why, then, are Pablo Picasso's women so often sulking, and why does Georges Braque keep painting nudes? Why do the artists insist on evoking classical music, through their centered, meditative compositions as well as all those violins? Braque even titles one painting Homage to JS Bach, with the composer's name lettered neatly across it. Paintings like this show uninterested in color, pageantry, or motion. Where film, like the pioneering stop-action photos of Eadweard Muybridge, presented a succession of large, discrete images, the Analytic Cubism of Picasso and Braque crosses small fragments of reality with even smaller stippling. Rarely has art yielded its clues so slowly, and rarely has it played so much to the mind.

The same disconnect appears with two other films, in alcoves to either side. One shows a high-tech world of airplanes, the other the comedy of manners in a Paris street. Why, then, did Picasso and Braque return to such old genres and low-tech subjects as still life, before Giorgio Morandi and others made it the task of a lifetime? Why did their breakthrough require a trip or two away from the modern city, to the Mediterranean coast? Perhaps they had to get away. Where film, like flight or the boulevards of Paris, offered a new perception of deep space, they flattened the image to the point that objects have nowhere to tumble but forward.

Opening with a sound film, in color no less, already signals trouble. The curator, Bernice Rose, argues that Picasso's circle went to the movies regularly, but starting in 1907, when movies did not exactly look and sound like Shrek. She insists on the influence of lighting, camera angles, and editing—some twenty years before Vertov, Eisenstein, and Chaplin. In reality, the color film came later and recreates a dance by Louise Fuller, not all that far from what Edouard Manet painted before the movies. Rose, formerly curator of drawings at the Modern, even takes it as a model for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. In her eyes, Picasso's crowded, confrontational brothel has become a refined one-woman performance.

The show repackages a persistent myth, of Cubism as about multiple points of view. At the time, however, Modernism's supporters and foes alike saw something more radical still—an assault on illusion, on any point of view, now that photography and film had illusions enough of their own. I prefer to see Cubism as remaking illusion, to the point of putting the whole idea of representation on the spot. It include traces of vision alongside symbols of text, music, transparency, and, in the artificial wood grain, even textures and scents. Memories collide, as in the avant-garde poetry that Picasso loved (and illustrated), but they rarely recur as one's eye scans the surface. Sure, the fourth dimension was in the air, but only because Einstein had redefined time and space as more than a succession of costume changes.

Blather about the new medium of film makes a new art harder to see, and the confusion also makes it harder to see what happened next. Thanks to Cubism, Futurism could celebrate the soul of the machine. Kazimir Malevich could imagining soaring above the earth as if in flight, and Nude Descending a Staircase, by Marcel Duchamp, really could pun on Cubism and motion. Worse, the show perpetuates the idea of technological determinism, much as David Hockney, the artist of California swimming pools, insists on reducing Jan Vermeer to a camera obscura—and much as some new-media artists mistake their data for nature itself.

Thankfully, Pace and Rose assemble a cabinet of wonders, with old cameras, nearly twenty paintings, and many more drawings and prints. (MoMA does not loan a thing.) One may not buy the story, but one gets to wonder what was, literally, in the air. One can also gets to see what does distinguish Cubism from film. Either way, Modernism comes newly into focus. Now if only one could focus on it without that annoying music.

Reweaving Matisse

"His Art and His Textiles"—when it comes to Henri Matisse, it sounds like a brilliant idea, until one tries actually to locate the idea. It really does sound, as an exhibition's other subtitle puts it, like "The Fabric of Dreams," until one tries to pin down the fabric or the dreams. A show on this theme that downplays his celebrated actual fabrics definitely has a problem, but what?

Certainly the painter's life had its own suggestive fabric, long before Rosemarie Trockel tried "knit paintings." He came from a family of weavers, in a town of woolen mills. His father, the Met notes, "acquired his business training in the textile departments of two leading Parisian stores." The exhibition proposes this background, along with his father's actual hardware business and his mother's personal counter there selecting and peddling pigments, as a counterweight to the artist's academic training. The Beaux-Arts tradition versus the artist's family—it could easily stand for the old story of drawing versus color, Picasso versus Matisse, or a rivalry within Modernism itself.

Once on his own, Matisse's encounter with decorative traditions only increased. He called Morocco a revelation, and he built his own costume collection, reflecting the influence of Spain as filtered through Manet and North African tapestry. Fabrics of every kind—tablecloths, shawls, blouses, and curtains—appear everywhere in his art. Even late in life, Matisse still turns to the decorative arts, with designs for vestments so tantalizingly close in spirit to his interest in such media as stained glass and paper cutouts. Matisse cutouts and other media lend not just color, texture, and patterning, but Modernism's characteristic visual, verbal, and conceptual dexterity. They allow the pictorial space to collapse onto the canvas or the canvas itself to open up into a space with a glorious, puzzling, or downright frightening emptiness behind its costumes and masques.

They allow Henri Matisse to let surfaces and textures veer suddenly into the things themselves or art to pun on art. They encourage, too, a new generation of art criticism to question hierarchies of taste, between fine arts and decoration. They make it harder to separate that classic male struggle in art history from women's work. In fact, they suggest transcendence of the opposition between, on the one hand, accounts of Modernism centered on formal devices, great artists, and a new vision of space and time and, on the other hand, revisions based on feminism, social class, commerce, and devices of appropriation. They invite one to stop quarreling over Modernism and Postmodernism, when one can instead be celebrating.

Yet I had to work hard indeed to find much cause for celebration at the Met. No doubt a focus on a painter's props is always asking for it, like the display cases in so many labored retrospectives. It invites one to see the artist's life and work alike as tired museum pieces—or exhibit A in Modernism on trial. It takes for granted that one can lump together the many ways that Matisse worked with his inspiration. It runs the risk, too, that the supposed inspiration itself will look disappointing or plain irrelevant. How strange to find that Matisse's uncanny fields of color, wide-open decorative swirls, and visual puns begin with the muted, straight-laced patterns one recognizes from any number of paintings, catalogs, and hotel lobbies.

A theme like this forces the issue in another regard as well: it means leaping from early work, by a half-formed painter not yet able to deconstruct his materials, to minor pieces by a comfortable older artist. So much for the centrality of textiles to a great painter's dreams. Even the introduction of Matisse's final forays into other media, which should come as the show's triumph, receive a token representation. The show originated at the Royal Academy. Perhaps, in opposing Beaux-Arts traditions to a craft's Rococo inheritance, it merely redoubles its ties to an academic version of modern art.

Human dynamo

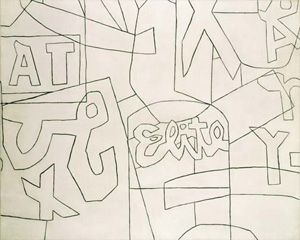

In his drawings, the career of Stuart Davis unfolds seamlessly, or at least one side of it does. On a single wall, one sees terse, precise studies. Here Davis's major paintings take shape over more than forty years, along with a uniquely American response to Cubism. Remarkably enough, his career then starts all over again on the facing wall, with sketchbooks—and then once more by the front desk, with large drawings from before 1920. Each start brings almost a different artist, and each brings Davis closer to the streets of the city. By the end, however, the dialectic has infected his entire work, over more than sixty sheets, and a good thing, too.

All along, his version of Cubism speaks in an American vernacular, quite as much as a landscape by Charles Burchfield. Where Picasso and Braque evoke the ephemera of late-night cafés, Davis prefers the architecture of Lower Manhattan by day. Conversely, where they take the long view, in echoes of "the primitive" or art of the museums, Davis's world is in constant motion. The curator, Mary Birmingham, calls the show "Dynamic Impulse," and the dynamic is clean, crisp, and even funny. When the artist designs a postage stamp, one line of text says FINE ART, another shouts POW! like Roy Lichtenstein, and another spells out nothing at all. Davis's impulse embraces both Modernism and comic strips, but it builds a momentum all its own.

The wall of studies naturally gives the clearest sense of Davis's painting. In 1921, with the artist not quite thirty, he arranges curved surfaces and planes at the center of a sheet like an exercise in solid geometry. It could represent a factory, but not as the oppressive capitalist idol of factories for Charles Demuth or Charles Sheeler, both barely a year younger. It could represent fragments from a pile of kitchen appliances, or it could point directly toward abstraction. The very second sheet comes even closer to pure abstraction, with cryptic lines beside translucent planes ascending at the right, but not without hints of windows in actual architecture. Davis's best-known paintings, also in studies here, combine all these ideas under titles like Eggbeater.

As he approaches those paintings, the lines, curves, planes, and lettering grow more and more cluttered. They also push more to the composition's edge. By the 1950s they start to flatten out, too, and by Davis's death in 1964 they have grown sparer and simpler as well. By the end, too, lettering runs every which way, from bare hints of calligraphy to suggestions of a tic-tac-toe game with only winners—or to a city's mad jumble of overheard conversations. In his Modernism, his mix of solid forms and surfaces, his all-over geometry, his pleasure in the ordinary, his sense of humor, and his sheer exuberance, he appealed particularly to Willem de Kooning. One can see them both as precursors of Pop Art.

It still comes as a surprise to turn to Davis's sketchbook—and his immersion in New York City. There he chooses more explicitly dynamic subjects, such as dockyards. The sketches date mostly to the 1930s, and one could write them off as the decade of social consciousness, the New Deal, and the WPA. Yet he pursued all sides of his work at once, and he really did mean a sketchbook as means toward his art. He scrawls indications of color, and he mostly applies them to open areas of the sheet, while human beings appear almost as infrequently as in his paintings. He is still thinking in terms of planes as well as objects, and he has a very American attachment to surfaces.

The small room for early drawings includes an actual comic strip from his teens, as well as drawings closer to the Ashcan school. One could describe Davis as first a comic artist, then under the tutelage of Robert Henri, then discovering Cubism, off to Paris in 1928, and finally back home to break free. Even here, however, things get jumbled up. The Armory Show, including Matisse, shook him up back in 1913, and one of his earliest drawings shows his modernist aspirations in another way—a brooding portrait of James Joyce in a crowded bar. Postmodernists might appreciate most the lettering, the way it spews out new associations and nonsense in equal measure, but also the way Davis often quotes himself along with what he sees on the streets. Fine art becomes a conversation that overruns the edge of the frame.

"Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism" ran at PaceWildenstein in midtown, through June 23, 2007. "Matisse: His Art and Textiles/The Fabric of Dreams" ran through September 2, 2005, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Dynamic Impulse: The Drawings of Stuart Davis" ran at Hollis Taggart, through January 12, 2008. A related review looks at a Stuart Davis retrospective.