The Idea of Manhattan

John Haberin New York City

Lothar Osterburg, Seher Shah, and Paul Graham

For T. S. Eliot, London was an unreal city, still shrouded in the brown fog of a nineteenth-century winter's day. Caught in the fragments of world literature, it could have been almost anywhere on the planet or anywhere in time. So what if Ezra Pound had commanded Modernism to "make it new"?

If any city were to follow to Pound's directions, it ought to be New York. And artists are still inventing it. For Lothar Osterburg, it still stands for a city of dreams, and it is still caught somewhere between a library and reality. He idealizes it and tries to remember it, only coated for his photographs in plaster dust and Surrealism. Meanwhile Seher Shah exhibits an ideal city or two on Orchard Street, right where galleries have stimulated some serious gentrification. As for Paul Graham, he photographs the New York right in front of him, but it, too, slips easily into the past or the future.

From Metropolis to Batman

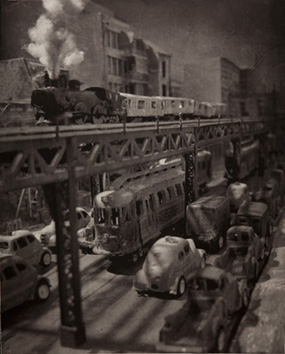

I can almost remember Lothar Osterburg's New York, except that it never existed. At least I want to remember it, the way one wants to recover a finer and more comforting past. It has the landmarks a New York native wants to call his own, like the Flatiron Building and tenements that gave way long ago. It has a child's wonder at the big city, like the lights burning in every window as they never have in real life. It has the darkness of an older city, too, like the shadows under the el spanning an entire street, much as it still does in parts of Harlem, Brooklyn, and Queens. I want it to be the train that took my father from the Grand Concourse to NYU dental school—although Manhattan's Third Avenue el came down in the 1950s, and the School of Visual Arts has that spot today.

Above all, this New York has books, although Yvonne Jacquette and Jacquette's New York have a whole library. They line the shelves of an old-world version of the great reading room at the central Public Library, a story or two too tall. They somehow share space with a trailer park, stacked as a still more precarious vertical. One book lies open in the foreground, as on a ledge, as mammoth as the Bible on a late medieval pulpit or the Koran on its stand in the Met's Islamic wing. Less directly, the entire show pays tribute to growing up with print, the kind that the artist pored over as a student in Germany. The photogravures divide into Yesterday's City of Tomorrow and Library Dreams, but the titles could almost be synonyms, and the two series could easily be one.

The second came about in collaboration with Osterburg's wife, Elizabeth Brown, a composer. The first brings the artist down to earth, after more ominous and obvious fantasies of outer space. Both begin with painstaking models in paper, plaster, and whatever else it takes. The miniature library is on display, too, along with the prints. Then he chooses an old-fashioned medium rather than straight photography. Its sepia and grain add texture and distance, as in fantasy or memory, but then so does plaster dust.

That dust shrouds early-model automobiles beneath the el, maybe one's first clue that these memories belong to others—or to no one at all. But then the Flatiron Building on Fifth Avenue never towered over the el, and trailer parks never stood nearby. I could not possibly remember the Sixth Avenue or Third Avenue el anyway, much less airships out of the 1933 "Century of Progress" Chicago World's Fair. The darkness of midtown south coming out of the 1970s was all too real, as in photographs by Jill Freedman. So were my own years in an illegal loft across from a topless bar not so very far away. Osterburg, though, describes longings for a past and a future that neither of us could have seen.

They take a certain will to believe even for the artist, who moved to New York in the mid-1990s and to the United States earlier still. One can imagine what urban America meant to someone elsewhere, which helps explain the setting in time, when immigrants still came through Ellis Island. This model city belongs to both continents, to Metropolis and to Batman. The locomotive bursting into the library belongs to René Magritte, who has it coming out of a European fireplace. Perhaps the entire show belongs to that painting's title, Time Transfixed. Of course, the point of that title for Magritte, too, is that time is slipping away.

Dioramas and prints shared space last year at the Museum of Arts and Design, in "Otherworldly," not a bad title for this show either. Do Ho Suh then made a miniature on an even grander scale, with a clearer fixation on the past. Both, however, were quite worldly at heart. The first like Lori Nix and Kathleen Gerber fixed on the artists' studios or a familiar America, including New York subways, while the latter combined his childhood home with his college town. James Casebere models real suburban anonymity. By contrast, Osterburg indulges in dreams that Modernism outgrew, but you may think that you remember them, too.

High treason

Modernism's hard edges haunt Seher Shah, but it has not lost its edge. Geometries divide and multiply her images, like memories. When she looks at a city, she sees concrete and social engineering, but she is also looking within. Masses hover over her photographs like threats, but also as monuments and mirrors. That makes "Object Anxiety" more whispery than anxious. It is a fitting monument to the fabric of a city all by itself.

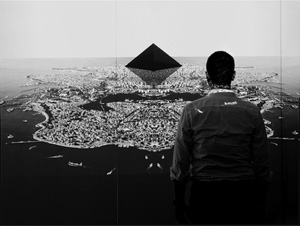

Maybe it is just coincidence that her show opened days before the September 11 National Memorial, but she shows a man overlooking a port city. It gleams with distant light off the water, on the edge between day and night. It could be an immense architectural model, like actual plans for the Long Island City waterfront, formed from hundreds of points of light. Not at all coincidentally, Shah lays out white trapezoidal pyramids on the floor. Both cities, in the photograph and in sculpture, are anonymous and familiar. I wanted to pick out where I was that day and where I lived.

Shah's vista is anonymous for good reason. It is reflected across a central vertical, like a human heart, and only the man displaced to the right breaks the symmetry. His unexplained presence holds it all at a distance, as do apparent vertical folds in the picture, as if he occupied an actual viewing platform behind panes of glass. Look again, too, and a cube resting on one corner has alit on the city, its upper tetrahedron black and its lower tetrahedron silvered like a mirror. He could be observing the urban design or lamenting it. He could be seeing his own reflection—or his own handiwork.

Shah's vista is anonymous for good reason. It is reflected across a central vertical, like a human heart, and only the man displaced to the right breaks the symmetry. His unexplained presence holds it all at a distance, as do apparent vertical folds in the picture, as if he occupied an actual viewing platform behind panes of glass. Look again, too, and a cube resting on one corner has alit on the city, its upper tetrahedron black and its lower tetrahedron silvered like a mirror. He could be observing the urban design or lamenting it. He could be seeing his own reflection—or his own handiwork.

Either way, he stands in for the viewer, and both artist and viewer gain from the identification. Born in Pakistan (like Salman Toor), Shah sees Modernism as authoritarian and destructive—and it may say something that she makes her observer male. In practice, she makes it hard to avoid shared responsibility for destruction. Others of her cityscapes replace the floating cube with decorative patterning. A tall black trapezoid descends on yet another city like a tombstone, an identification that Shah makes clear with photographs of graves and rituals. In her hands, Brutalism and its concrete walls have become transparent, much as Scott Burton made them into public spaces. Death is somber, but a ritual is a remembrance.

Scale models have a way of evoking grandeur, not to mention nostalgia. Think of the miniature New York at the Queens Museum. No matter how often the museum updates the model, it will always come laden with its origins in a World's Fair—a celebration of modernity. Shah also sketches Unité d'Habitation, Le Corbusier's utopian but disastrous housing project in Marseille, and the drawing's sheer size pays homage to his ambitions. Typically, too, looking down on a city combines tribute and self-reflection. Think of how often photographs of Ground Zero adopt that point of view.

Shah calls the initial photo Cross Conference Scheme from the Manual for Treason, like a blow against Brutalism's empire. And she means it—only I cannot help imagining other meanings and other intentions. Shah nurtures them despite herself, just as she nurtures contradictions and symmetry breaking. Speaking personally, I shall take Marcel Breuer's Whitney Museum (even after the Whitney abandons it for the Meatpacking District), a triumph of Brutalism, over the former World Trade Center's columns and skin any day. But that descending black slab is gloriously high treason. In light of an old subway map, it even resembles Manhattan.

Past, present, and future

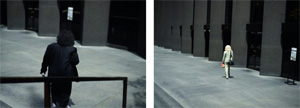

Paul Graham hardly bothers to compose his photographs, and then he composes them. At least he brings them together in series that, as it happens, never quite compose themselves either. The results can be tantalizing, frustrating, or both at once. His latest gain in resonance by shifting to Manhattan business districts, where workday routines add to the sense of both rootedness and dislocation. He also works larger, with series reduced to two wide frames, inviting more focused attention. They also shift more of the burden of storytelling to the viewer.

The carelessness may sound like the amateur confessions of a blogger or Pinterest, and series may sound uncomfortably like albums on Facebook. Graham long shared another feature of the Web as well, something of a message. Born in 1956, he hit New York in his forties, after years documenting Thatcher's England like Brian Griffin. Naturally he went in search of America, like Walker Evans, Robert Frank, or Lee Friedlander before him (and as "framed by Joel Coen" years later), with a fondness for bright sunlight and color film like Joel Sternfeld. Maybe he came too late for the party, but mostly he acknowledged a British lack of interest in the open road. He got out of the car to study houses, faces, and that American dilemma that must seem especially peculiar to someone from elsewhere, race.

"American Night," exhibited in 2002, made it obvious—a little too obvious. He bleached African American residences to a faded white, made the other single-family houses seem all the emptier and whiter, and shot blacks as trapped even in motion. "a shimmer of possibility" from 2006 then crossed the country to some of the familiar suspects, like Vegas, while developing the method of work in series. A black crouches in profile while eating something unappetizing, hands cling to a coffee cup, and a man seems stuck mowing not a lawn but the entire landscape surrounding a highway. In a nation as stratified as this one, a shimmer of possibility may be close to none at all, hardly worth the dignity of initial capital letters. The series suggest untitled film stills, from a movie one may not wish to recall.

Graham calls his latest the conclusion of a trilogy, and the return to the city is like a homecoming. Not that he belongs here—no more, he implies, than anyone else. Still, the big diptychs and occasional triptych get one lingering, if only to try to get one's bearings. They also get one working a little harder to draw connections. Not that race and class are out of the picture, but if you see them, maybe the American stereotypes belongs to you. "The Present" is less like Harry Callahan and classic street photography than one of those novels in the present tense, with you as the unreliable narrator.

A black man in a business suit strides confidently, and then, an unknown number of moments earlier or later, a clearly poorer black man hunches forward almost to the point of falling. Who, they seem to say, is dogging whose history, and who are your prejudices willing to accept? It says something that Graham can now pull off so pat a pairing without dragging things down. In fact, it is for me the show's lasting image—along with two women seen from the rear, one black and one blond, one heavy and one fashionably slim, the office plaza behind them almost out of Giorgio de Chirico. Still, after that things are more and more up to you.

Banal or memorable, pairings can shift point of view slightly, or people can move in and out of the frame. What I took for a woman with a cane turns out to walk quite ably on her own, while leaving the person with a cane behind her. A woman in the crouch of the homeless is a nurse on a break, while someone less able to fend for himself crosses in front. A young man looking up could be oblivious to those less dressed for success, but then he could be the one with time and insight to appreciate the city and the sky. Someone on the borders of one frame can become the star, if only for the moment. The present is about to become past and about to hold the future.

Lothar Osterburg ran at Lesley Heller through March 4, 2012, Paul Graham at Pace through March 24, 2012. Seher Shah ran at Scaramouche through October 30, 2011.