Never Let Her Go

John Haberin New York City

Elizabeth Catlett and Michael Armitage

Jacob Lawrence: Builders

Elizabeth Catlett found her subject early and never let her go. It allowed her art to span a tumultuous century and then some. It made her "A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies," at the Brooklyn Museum.

Late in a groundbreaking career, Jacob Lawrence and his Builders poured a comparable empathy and energy into the black male. Of course, you may know Lawrence better better from an epic series, The Migration. A contemporary black artist, Michael Armitage, paints a more dangerous migration—not from the American South, but from Africa.

What it implies

Catlett was warm in her feelings but relentless. Her work on The Negro Woman, later renamed The Black Woman, takes up the entirety of an awkward but impressive gallery. She hammers it home to her own heart in cedar and in oil, starting in 1942, before releasing it as fifteen prints the next year.  Side galleries show her as a student at Howard University at just seventeen and a teacher in New Orleans, but her style and her command are in place. Portrait heads to each side range to leading figures in black history, men and women, but they seem like an extension of the same capacious series. She lived until 2012, but one might easily think that her career lasted just five years.

Side galleries show her as a student at Howard University at just seventeen and a teacher in New Orleans, but her style and her command are in place. Portrait heads to each side range to leading figures in black history, men and women, but they seem like an extension of the same capacious series. She lived until 2012, but one might easily think that her career lasted just five years.

So when did she find herself? It could have been as a student, already skilled in drawing. In her training, as in her subject matter, Catlett left nothing to chance. It could have been as jobs and education took her to so much of North and South—including New York, where she exhibited in a 1943 show of "Young Negro Art" at MoMA along with Charles White, just in time for the Harlem Renaissance. It could have been in exposure to other artists as well. Barbara Hepworth and William Zorach showed her the blunt impact of sculpture as little more than a block of wood. Käthe Kollwitz, Grant Wood, and Pablo Picasso showed her painting as personal, populist, and "the primitive."

It could have been as a child in Washington, D.C., born in Freedman's hospital to a family that had known slavery. She observed women in all their strength, but the restrictions that they faced as well. Her 1943 series includes a sharecropper and a woman scrubbing floors, as I Have Always Worked Hard in America. Yet it also includes a woman behind a barbed-wire fence, as My Reward Has Been Bars. Mostly, though, she depicts anonymous women, facing ahead or looking upward for something more. They are portraits not of individuals, but of determination. Catlett is always accusing, but never short of hope.

Or maybe she found herself as a young woman just by looking in a mirror. She decided she had what it took, and that was that. Still, she approached her students as collaborators, hanging salon style the portraits from history. She embraced the cause of black women, but also of worker's rights. No wonder she headed in 1946 for Mexico, where the revolution promised socialism and the Taller de Gráfica Popular (or Graphics Workshop for the People) did its best to deliver. She stayed until a comparable activism and popular spirit in the 1960s came to the United States.

At least she thought so, and her career took a new turn at last. Those first rooms surround The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago and have often hosted art by black women, including Beverly Buchanan and Lorraine O'Grady. Yet the show continues past twin doors with an artist in her fifties in support of civil rights and the Black Panthers alike. Catlett's prints adapt easily to posters and her carvings to standing figures or a fist. She adopted linocuts long before for the jagged outlines of woodcuts and the ease of freehand drawing. As curators, Dalila Scruggs, Catherine Morris, and Mary Lee Corlett place them around a large platform for sculpture.

In truth, "all that it implies" may not be very much, but it could well be enough. The Black Woman gives the show its drive and its place in the history books. The coda loosens things up. When another sculpture, a family, floats overhead, Catlett might almost be having fun. Still, some things never change. With a self-portrait on paper in 1999, she is still facing front.

Groundbreaking

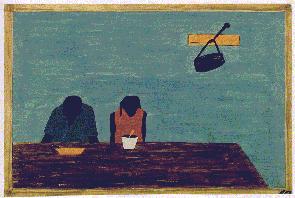

Jacob Lawrence looked up from his work and had a revelation. The tools of his trade were everywhere around him, and suddenly they meant something more. They were tools that he shared with others, the very people he painted—African Americans creating a place for themselves in America. These people created a community as well, a community of builders. In more than one sense, they were breaking ground themselves. Soon, too, they became the subject of Builders, in 1998 and at that very gallery today.

Of course, that sudden revelation never took place. Lawrence identified all along with his subjects and saw them as builders. It took decades for black Americans to claim their rightful place, a task that is still far from complete. He first described the community as itself a work in progress. You can see it in the titles of his most famous paintings, The Migration Series and Struggle. He was also a perfectly self-aware and reflective artist, happy enough to paint a compass and right-angle straightedge, with all the rigor they brought to drawing. He could see perfectly well that the same plane in a carpenter's toolkit served him to make a stretcher and to make its edges clean.

Of course, that sudden revelation never took place. Lawrence identified all along with his subjects and saw them as builders. It took decades for black Americans to claim their rightful place, a task that is still far from complete. He first described the community as itself a work in progress. You can see it in the titles of his most famous paintings, The Migration Series and Struggle. He was also a perfectly self-aware and reflective artist, happy enough to paint a compass and right-angle straightedge, with all the rigor they brought to drawing. He could see perfectly well that the same plane in a carpenter's toolkit served him to make a stretcher and to make its edges clean.

When it comes down to it, Builders was only a coda to thirty years of relative decline. He painted the Great Migration from the rural south in tempera on sixty small panels in 1941, when he was just twenty-three, and his history of the American people as a struggle in 1954. His paintings of builders came just two years before his death in 2000. Perhaps he felt it as a renewal. He could go back to the flat bright colors and fields of black that he had introduced in tempera, but now he could apply drawing and color to a building. He could in turn apply those same patterns and colors to human flesh.

If Lawrence identified with his work and with a builder, he identified the builder's work with the worker. Unfortunately, the gallery exhibits just one of twelve paintings together with work on paper, but it makes the point well. Buildings tilt at improbable angles, flattening the entire painted surface, while conveying mass and depth. They claims his work for both Modernism and realism. They give new meaning to formalism, too, with a carpenter's insistence on form. And then the same brickwork covers the people, painterly brick by brick.

Still, I like to imagine a moment of discovery. I first saw The Migration Series in 1995, when it came as a revelation to me. (It led to one of the first reviews on this Web site.) The Met back then exhibited the series and Wassily Kandinsky in adjacent galleries, demanding a choice on the way in. Art history, it seemed to say, had made its choice, excluding a black man's seeming crudeness in favor of Europe's relentless experiment, and it was time to look at history anew. Besides, Kandinsky's wild horses are a kind of folk art in themselves.

These days The Migration Series is on display in its entirety nearly all the time, in MoMA's collection. Lawrence, though, is still looking back. He respected old-fashioned studio training, and he could use it to recall an African American's roots. The gallery displays some of his weathered tools along with works in charcoal, pencil, and gouache, and their wood would never make it into a hardware store today. And yet the same care that goes into a builder's anatomy powers wild, fragmentary shapes and colors. Storytelling approaches abstraction. And the white of a black man's eyes matches the ghostly silhouettes of his tools.

A dangerous crossing

Michael Armitage paints refugees on a dangerous crossing. Fortunately, they still have each other—unless that is the worst of the dangers. For his latest work, he takes as his theme the passage from Africa, a theme that he must take personally. Born in Nairobi, he lives and works in London. Those who know his work will recognize the wild confusion of his narratives and the straight-on encounters in his portraits. More than before, though, that translates into political commitment and heart-felt sympathy.

Armitage himself had a perfectly safe crossing—or as safe a crossing as an African can expect. He came to London to study at its finest art colleges, and he has made a successful crossing to America as well, appearing in a show of black artists at MoMA. He terms himself with a Kenyan Brit, and you can hear the confidence in his cultural heritage. Few are as certain that they can claim both Africa and the West. He paints on Ugandan bark and called his last show, in Germany, "Pathos and Twilight of the Idle," challenging the uninitiated to spot the pun on Friedrich Nietzsche and Twilight of the Idols. If you feel a certain condescension, so be it.

The show is his "Crucible," another boast. The Crucible is a play by Arthur Miller about the Salem witch trials, and Africans are dying because of prejudice now as well. Armitage asks to see a crucible as more than a watery journey. Its meanings broaden to the very concept of a dangerous passage and to metaphor. It returns the word to its more common meaning as a test or trial. People, he can hope, emerge stronger and more able to speak for themselves.

He calls a sculpture a near synonym, Trial, another boast of a European heritage. The Trial is a novel by Franz Kafka with a deadly ending, and here, too, individuals are caught in narratives that they may not survive and will never understand. I had not seen the artist's sculpture before, but he places it first, with priority to its blackness. The cramped space of sculpture in low relief has its counterpart in the familiar space of his paintings as well. They include standing portraits and imaginings, in open waters, neighborhoods of London, and indefinite space. You may have to shift perspective after discovering which is which.

Three boys have found their way to shore at night, beneath turbulent clouds, stars, and artificial light. Should they take comfort in each other? Two of them hold the third, who can no longer to stand on his own—unless they are keeping him from finding escape. Friendships for Armitage are treacherous crossings, too. Sometimes small groups sit side by side, as eerie clusters of green, although flesh tones are normal enough. Shadows on naked flesh take an ominous shape, like skin that has away.

Distortions like these recall the agony in artists like Francis Bacon, R. B. Kitaj, and Lucien Freud. Armitage may have a British heritage after all. And that heritage extends to an all but exclusive focus on narrative and faces. I find that focus conservative and confining, like a test. Still, he has something that they do not, primary colors in daylight and blackness out of Africa. Just remember to rely on one another.

Elizabeth Catlett ran at the Brooklyn Museum through January 19, 2025, Michael Armitage at David Zwirner through June 17. Jacob Lawrence ran at D. C. Moore through September 28, 2024. A related review looks at Jacob Lawrence and his "Migration Series."