Like He Never Left

John Haberin New York City

Grant Wood and American Gothic

Nick Mauss: Modernism and Dance

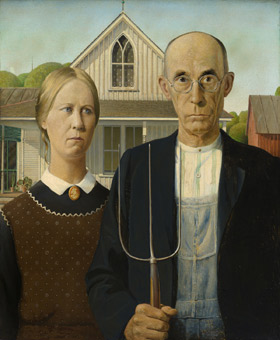

You may be delighted that the Whitney has placed American Gothic at the very heart of its retrospective of Grant Wood. If you are like many Americans, it has come to stand for your country. You may count it among your favorite paintings.

Then again, you may be leery or worse. You know why art like this so often gets no end of parodies and no respect. You may distrust the stereotypes of a farmer and his wife or (by some accounts) daughter—and the mythic past to which they belong. America, you may think, is still paying the price for believing in it. You may want to consign it to history, or you may want instead to look past it to the realities of 1930 or today. You may want to see in its harsh edges and harsher faces the austerity of the Great Depression.

Then, too, you may wonder how it reflects on your history. Would the pitchfork, artfully echoed in the man's work clothes, and the hand that clutches it have turned on you? Right out there in the picture plane and at dead center of the canvas, its tines could pierce you in a minute and throw you away. Do the man's sour expression and the woman's wary scowl show how little they accept you? Would the whitewashed house with church windows behind them have turned you away? Its sole gothic window has its only radiance, and the red barn to its side has no doors.

Whatever your thoughts, you are in good company. Grant Wood might have shared them all and more. Born in 1891, he revered farm country from his childhood in Iowa, and he knew these people well. He returned to Cedar Rapids after studies in Minneapolis, starting a career in Park Ridge near Chicago, and four visits to Paris in the 1920s. It was like he never left. As a postscript, the Whitney looks at more of its holdings from those years through the eyes of Nick Mauss and "interpretive communities"—and that does not mean eastern Iowa.

Idealism and satire

Then again, it was like Grant Wood was never altogether there. The museum sees him as quite possibly a closeted gay male struggling for acceptance. It shows him breaking through with a prize winner, now in the Art Institute of Chicago, only to face lost commissions and charges of pornography. It finds him alternately enshrining, satirizing, and fearing American myths, and it dares you to decide when he did which. Its title, "American Gothic and Other Fables," is only partly a debunking. It is also about the tensions in him.

The show itself has a disturbing dual identity. A dark wall directs one forward, with the promise to put the American in Gothic. To the side, though, one can see ordinary white walls and a perfectly ordinary retrospective. You choose, and no one will blame you for choosing the straight and narrow, much like Wood. You will not, though, see his most famous painting right away. That first dark room already holds a puzzling mix.

It holds his wan experiments with Impressionism in Paris, already long past the real thing. Yet it also has the more sober realism of memorial windows to honor those who served in World War I. Their stained glass looks more ghostly than translucent and colorful, as an unsettling reminder of the dead. They also introduce Wood's unspoken torments. A bare-chested soldier could be a sex object or a corpse. Did the artist know his desires from his fears?

Most of all, the room has decorative art, including a lampshade and shelf after shelf of pitchers and other work in silver. (Wood titled a painting Ornamental Decoration as well.) A few ceramics have a clumsy refusal of function, like early Alexander Calder. The curators, Barbara Haskell with Sarah Humphreville, speak of Wood as getting over a belief in Europe's cultural superiority, but he never quite bought into it in the first place. He started with the proud American self-assertion of the Arts and Craft movement, an influence on Frank Lloyd Wright as well. Early paintings proclaim the four degrees of Freemasonry and Adoration of the Home.

Home is where the heart is, and Wood's heart is always torn. Even when he encounters Hans Memling and Albrecht Dürer in Europe, they are his means to break free from Impressionism on his way back home. Other early work focuses on single figures, like a woman with a plant and a man in a business suit, labeled a "pioneer." He must have been already longing for farm country and for leaders. He must have feared them as well. Victorian Survival depicts an aunt with a preternaturally long, stiff neck and a telephone, as if unable to decide between the Victorian age and modernity.

He is also starting to face the choice between idealism and satire. Haskell links the telephone to a spinster's role as a gossip, but then Wood might have been on board with that role, too. Three more dour women pose in front of a painting even more beloved than American Gothic, Emanuel Leutze's Washington Crossing the Delaware. Wood's audience praised it for its canny critique of the Daughters of the American Revolution, but it looks not all that different from another group portrait, of a Shriners vocal quartet. Wood makes them starry-eyed, foolish, and endearing. And he dedicates himself to several more American myths, only starting with American Gothic.

Unremitting stares

One comes face to face with it at the end of the two dark rooms, ready at last to turn to the main galleries. It gives Wood his first brighter palette, firmer edges, a clear composition, and a lasting myth. Before long he added at least two more. One painting shows Paul Revere's midnight ride, another George Washington as a boy confessing to having chopped down the cherry tree. Parson Weems, who popularized the story, pulls aside a stage curtain as if winking at the fiction. Yet Wood seems to have bought into it and begged for more.

He also begged for an audience. He designed a children's book and murals honoring Agricultural Science and Fruits of Iowa. He illustrated Main Street, the searing portrait by Sinclair Lewis of Middle America, but he wanted a broader appeal as well. He painted a communal dinner for threshers, in hopes of catching the eye of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. Yet he also painted the birthplace of Herbert Hoover. He went without a sale.

His audience might not have seen through his praise, but they must have felt its limits. Wood's farmers come with their pigs and women with their chickens. They seem oblivious to the near isolation of a child in their midst. Hoover's birthplace includes a shadowy tree-lined arcade and a lone tiny figure pointing home. The charges of pornography dogged bare-chested men doused in water. He rarely comes that close again to sexuality.

Still, he starts to acknowledge the upheavals within. They bring him not so far after all from the dark magic of Edward Hopper, Hopper drawings, and American Surrealism or the American scene of Thomas Hart Benton. For Death on Ridge Road, a fancy car trails a black hearse and a looming red truck, as if another accident is about to take place. A storm gathers as well. For a series on the four seasons, snow-capped sheaves of wheat stand as inhospitable shelters. Horses cannot escape barbed wire.

Wood developed in another way, too, toward bulging masses, a muted finish, almost akin to tempera, on both canvas and panel. Wood took enormous care with each work, often with full-scale studies in chalk, charcoal, and pencil. (His sister and his dentist posed for American Gothic. Did they appreciate the compliment?) The studies are as polished as the finished paintings. Their very polish could be one more way of subduing his fears.

He had barely a decade to try, before his death from cancer in 1942. He never comes close to Modernism and an urban present, and he never fully scrutinizes his feelings. He never takes on the sweep of America in Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler—or the very thought that his country's color could be anything but white. The woman in American Gothic can never match the taut realism of an Alabama tenant farmer's wife by Walker Evans, although it anticipates her by six years. He will always be the painter of Return from Bohemia in 1935, with Europe and the avant-garde as a distant scandal. Still, he could never return home without encountering a pitchfork, a shuttered church, and unremitting stares.

Interpretive dance

In the 1980s, at the very moment that Modernism was shattering into competing in-groups, critics were speaking of interpretive communities: it takes both readers and writers together to create the conditions for seeing. It may be just a coincidence, but Postmodernism seemed out to confirm much the same for viewers and artists. Now Nick Mauss finds an even livelier creative interchange between modern artists and dancers, starting well before Alvin Ailey with the American Dance Theater, Robert Rauschenberg with Trisha Brown, or Tiona Nekkia McClodden with Dance Black America. For him, the ultimate interpretive community is a dance company. He invites the Whitney and its visitors to join the community as well.

The show features his own collaboration and reinterpretation. For four hours each day, twelve dancers perform, four at a time. They take it slow, in seeming trial movements. They might be in rehearsal or at rest while others continue. Around them are the artist's sources, from dance archives and the museum's collection. They run to far more than choreographers and dancers.

Artists here take on multiple roles, and the connections run in both directions. Paul Cadmus paints another quiet moment in a dance studio, but he also designed the costumes seen in photographs and a recreation. Dorothea Tanning did costume design, too, as did Pavel Tchelitchew, restraining the American Surrealism in their paintings. Joseph Cornell contributed the cover to a history of dance by Lincoln Kirstein (who also sat for Walker Evans). Gaston Lachaise looked to dance for his sculpture, like Edgar Degas before him but more massive and murkier. A set for George Balanchine appears here as an ominous work of art.

John Storrs may not have had dance in mind for his Cubism or Man Ray for his c-clamp clutching a silvery tower, but Mauss found inspiration in them as well. He pored over the museum's holdings with the curators, Scott Rothkopf and Elisabeth Sussman with Greta Hartenstein and Allie Tepper. He even throws in an earlier recreation. Sturtevant, who paid tribute to Marcel Duchamp for the 2006 Whitney Biennial, restaged in 1967 the cancellation (owing to a dancer's illness) of a 1924 ballet by Francis Picabia with music by Erik Satie, film by René Clair, and a passing appearance by Duchamp himself. Picabia hardly knew what was coming when he called the ballet Relâche (or "canceled"). Nor did ticket holders unsure whether they had seen a performance after all.

All this punning and repetition sounds postmodern enough, but Mauss is anything but critical. He calls the show "Transmissions," because the present reinvents the past for the future. A figure from the American Negro Ballet, in front of floral wallpaper, could be competing with white dancers in a slide show by Carl Van Vechten—or with President Obama in his official portrait by Kehinde Wiley. As I watched, a guard was moving her arms to join, however modestly, in the dance. Mauss shows his own hand only once, in painting on silvered glass that mirrors its surroundings. He may remake history most, though, just outside the entrance.

Film on pale hanging scrim documents Russian touring companies from the 1930s through the 1950s. To either side, George Platt Lyons photographs the New York City ballet in 1936, for Kirstein. Hans Bellmer might have posed the twisted bodies, Robert Mapplethorpe the nude flaunting his penis. A woman wears only heavy cut paper, almost like Yoko Ono in fabric for her Cut Piece. With his mock period room for the 2012 Whitney Biennial, Mauss may seem mired in the past or in his head, but he may yet have found a way out. Still in his thirties, he falls back on his tastes and his research, but through an interpretive community.

Grant Wood ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through June 10, 2018, Nick Mauss through May 14.