Framing Blackness

John Haberin New York City

Lorraine O'Grady and Cy Gavin

When it comes to race and gender, has anything changed in thirty years? Perhaps, but then so has art.

Lorraine O'Grady had a way of hogging the spotlight. There she is, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, in her white dress and perfect poise, invading galleries (as she liked to put it) because what else is there for a black woman artist to do? She is on center stage, because the art world is on the spot. And yet, in much of her work, she cedes the stage to others, who pose as they wish in gilded frames. It is the African American Day Parade, with marchers, spectators, and cops enjoying their moment in the spotlight and in art. You may find it hard to decide which memory is the real O'Grady, in the frame or out, or the reality of race in America—but a retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum invites you to see not either/or, but "Both/And."

Five years ago, a return of the parade photos already had one looking to art and race in the present. O'Grady photographed African Americans when "theory" was a buzzword and critique was a demand. Shortly before, Cy Gavin painted a gay black male when, in painting if not in life, pretty much anything goes. She uses art to comment on itself and to frame others, while he puts himself at the center of the frame. She asserts her pride while allowing others to perform and to play, whereas he keeps silent, at least on canvas, while seeming at once to laugh at himself and to cry in pain. Identity is as complicated as ever.

The woman in white

Not that you need remember Lorraine O'Grady from the early 1980s to admire her retrospective. Yet the black woman in white and the gilded frames are hard to forget. She fashioned her long dress from a hundred eighty pairs of white gloves, with a beauty-contest sash to hold her fictive name. Her invasions made quite a splash, too, starting at an all-white gallery, shouting protest poems and whipping herself like a plantation slave. The other work, Art Is . . ., has become a paradigm of protest art, as in "Zero Tolerance" a few years ago at MoMA PS1. Just months later, it had a show to itself at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Just how different are they? Both have their glitter, and both are pioneering black performance art. O'Grady herself joined the parade in character, although she stayed out of the photographic picture. Both, too, are about black identity and exclusion, but also about what art is. The title of each photo proposes a different answer, with her usual care for words. Later work, with strategic displays throughout the museum, consists of clips from the New York Times as politically charged found poetry.

Then, too, both early works are about inclusion, the "both/and." Her invasion sites included a show of black artists to probe its rules for selections. Once inside, too, she found not just confrontations, but occasions for a party, mingling over drinks. Nor is a parade simply a protest, no more than for the Harlem of Dawoud Bey, and politicians are notably absent. Equal numbers of blacks and whites served as collaborators, taking the photos and holding the frames. White cops joined right in.

Rivers, First Draft or the Woman in Red combines her twin stories. Here the star is a multiracial city and the north end of Central Park. The woman in white is back, seated in a clearing, consuming a coconut or setting down her thoughts. The woman in red is half of a white couple, cuddling on a rock or darting past trees. A fourth series brings out the comedy and the longing, as The Body Is the Ground of My Experience. A white mannequin attempts sexual assault distant, bored, and self-aware black woman, while a house on wheels pays tribute to O'Grady's Jamaican mother in exile, in transit, and at last at home in Boston.

Those years came to an end, and so for the most part did her work apart from teaching and writing. Since then a woman on video, perhaps the artist, combs her African American hair. Hung with the Hudson River School in the permanent collection, it asks about blackness, American art, a woman's body, and its traditional identification with landscape—but a woman's voice seems strangely absent. Photos in the grand third-floor rotunda pose their Family Portrait in medieval armor. They, too, ask who belongs in a museum and who are today's superheroes, but only barely. Cutting Out the New York Times has its hits, like "Summer Is Being Held Over until the Sun Dies," and its glib misses.

The show's quiet ending had me thinking less of black women artists like Nellie Mae Rowe, the reserved and the proud, than of Yoko Ono. She, too, began in performance with herself on the line, before years of text art that have yet to bring about world peace. O'Grady, though, seems to have known when to pass the torch and the picture frames on to others. Her early works still look as humane and as daring as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire herself—a performance she continued at the black-run gallery Just Above Midtown. The parade also makes a pointed contrast to summer protests for Black Lives Matter, where police lived up to their sorry image. Male or female, black or white, you can still be demanding inclusion for all—and still asking what art is.

I love a parade

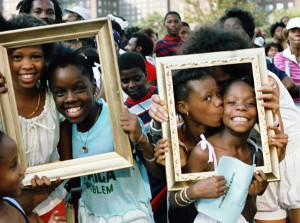

How can art frame a life? Should it speak of an individual or a community, race or gender, youth or age, or what people see in each other as a day grows long? Does life lie most in the streets they inhabit, what they wear, where they go for dinner, or how they spend the late hours of the night? Or is it all just a parade? For O'Grady, it is all of that, only she provides the frames. Back in 1983, for the African American Day parade, she outfitted performers in white—and all of them carried picture frames.

The result was Art Is . . ., and its return makes the case for the Studio Museum's planned expansion, announced just days before the opening. Its forty photographs have the basement galleries, normally reserved for the permanent collection, which has nowhere else to go. The room just outside has photos by high school students with their own multiple lives. They run to natural light and personal memories. The museum mixes them with photos of Harlem from the 1920s by James VanDerBeek, who started the museum's studio program long ago. His pool hall, each table with its triangle of balls, is the ultimate in geometric abstraction, only waiting for the break.

O'Grady was trying something just as audacious—to express the lives of others, with her own array of rectangles, but as a performance of her own making. The series has become a paradigm of political art for those who reduce politics to parades and marches, as in "Zero Tolerance" at MoMA PS1. One and all, after all, are taking part in a celebration of racial identity. The performers in white are dressed for fashion or a wedding, while marchers are dressed for the streets. This could be The Americans, the vision of an entire country by Robert Frank, but for African Americans. Yet it is first and foremost about people.

The photos do document an uptown community, because the parade walks right through it. Awnings for food and nightlife testify to hours and lives that one cannot see. At the same time, a parade is out to forget all that. Marchers head for sunlight, company, a long walk, and a good time, and the photos attend to those as well. People stroll, and the performers approach a dance. Public speakers are nowhere to be seen.

O'Grady puts everyone on the spot, but everyone, too, seems eager to join in. While performers hold the picture frames, their subjects reach for them, too, to frame themselves and loved ones. A boy thrusts an arm right through one, but O'Grady is already breaking the picture plane, as the frames multiply like images in a mirror. A white cop eyes a young black man, but elsewhere a policeman stands apart from the performance, with an awkward smile. Then, too, someone else again is framing these frames, with a camera. The floats, windowed buildings in the background, and lanes for traffic add their frames as well.

Maybe you get to decide among them, or maybe not. Plainly the photographer directs the lives of others, and a parade float serves as a stage. O'Grady earned attention earlier in the 1980s, with more overtly gendered and political work, in a decade of irony and the "Pictures generation." Later, for the 2010 Whitney Biennial, she paired images of Michael Jackson and Charles Baudelaire—who called his Haitian mistress his "black Venus." Still, here she leaves art as open-ended as the work's title. Others, too, can choose their frames.

Dreams of a father

When Barack Obama called his account of his early years Dreams from My Father, he allowed himself to share in his father's dreams. And then he let himself imagine that, all along, his father was dreaming of him. Turning thirty, Cy Gavin is still making an "Overture," even after his father's death. In a show named just that, he creates narratives of them both in paint. They never appear together, and they may never overcome their isolation. Yet there, too, he acts out a dream of connection, in which a life ends only to give way to another.

Father and son share pitch black skin and hellish landscapes. Southern trees look on fire and Bermuda locked in an icy sea. And then the two men dive right in, damn the consequences. The father tumbles backward into an open pit, arms flung wide in helplessness and fear. The son immerses himself in arctic waters, hands raised as if in prayer. Both are determined to stick it out, well after the macho posturing of a Kehinde Wiley and Wiley's public sculpture falls away.

Father and son share pitch black skin and hellish landscapes. Southern trees look on fire and Bermuda locked in an icy sea. And then the two men dive right in, damn the consequences. The father tumbles backward into an open pit, arms flung wide in helplessness and fear. The son immerses himself in arctic waters, hands raised as if in prayer. Both are determined to stick it out, well after the macho posturing of a Kehinde Wiley and Wiley's public sculpture falls away.

Gavin may sound over the top, but one cannot spell overture without overt. Besides, he brings a hellish sense of humor. He morphs into a bear in pointy shoes for Black, Black, Black Is the Color of My True Love's Hair. His spirit hovers in outline in another painting like Casper the friendly ghost. He makes his landscapes vivid and painterly, with acrylic and oil that approach the fluid brightness of watercolor. J. M. W. Turner comes to mind, with much the same dichotomy of fire and ice.

The landscapes look familiar enough from Western painting and Western narratives, for all their polar extremes—just as "Black Is the Color of My True Love's Hair" is an American folk song, Kerry James Marshall has taken the barber shop as the locus of African American community, and blackness has a dark place in America's history. The open pit has the brutality of a strip mine. Still, the painter also mixes in hair, diamonds, pink sand, and his father's ashes. He incorporates blood, too, like Wangechi Mutu, Bathélémy Toguo, and other African American artists, not to mention David Wojnarowicz. Staples or pins outline some bodies as well. Gavin has painted his subjects, in two dimensions, but they force themselves on his imagination like a rough collage.

Gavin sees identity in terms of doubling. It runs to gender, generations, and, of course, race. The staples refer to an African ritual of exchanging bodies for "spirit vessels," but they come mass-produced in America. He quotes The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois: "one ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder." If he has the strength for that, he can endure a painting, a funeral, and a block of ice.

Clearly he has the body on his mind. If he is slow in making overtures, he is, I gather, a gay male from a Pennsylvania family of Jehovah's Witnesses—not too far from the roots of that Appalachian folk song. His father's dreams could not have had much room for him. In Homecoming, the bear-like figure crawls across a landscape with, literally, no place like home. But then Obama, too, had only an absent father, who died when the future president was just twenty-two. He did not even get to scatter his father's ashes in paint.

Lorraine O'Grady ran at The Brooklyn Museum through July 18, 2021, and at the Studio Museum in Harlem through March 6, 2016, Cy Gavin at Sargent's Daughters through August 20, 2015.