Higher Things

John Haberin New York City

Tom Sachs and Folly: Curtain

Can a tea ceremony come to Mars and a vision of heaven to New Jersey? Tom Sachs sets his mind on higher things.

Sachs is not expecting miracles, but he is ready for a ritual. At the Park Avenue Armory, he requires "indoctrination" into the artist's self-absorbed fantasies. Do not cut class quite so quickly, though. His dreams echo in other urban visions and follies, in Socrates Sculpture Park. Besides, like all of Modernism's utopias, he is not altogether dreaming. There and at the Isamu Noguchi Museum, you can see him as pursuing an ancient art or hard science.

Tea for one

Tom Sachs is happy with a large museum installation—and with himself. Already in 2012, he took over the venerable Park Avenue Armory as a purported gateway to outer space. Now he aspires to the serenity of the Isamu Noguchi Museum and a tea ceremony. Can he set aside his titanic ego long enough to kneel in harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility? Can he avoid sneaking some booze and a Big Mac into the garden? Of course not, and one can hear him laughing all the way to the banks of the Tonegawa.

His private mission to Mars never left the ground, so why should one expect more from Tea Ceremony? Whatever is he doing here in the first place? Where Isamu Noguchi nurtures maturity and silence in Modernism, much as in his influence on Gonzalo Fonseca, Sachs is among the noisiest and most adolescent of postmoderns. Where the one bridges eastern and western traditions, the other looks to Japan and sees only another site for the golden arches. Where the first designed his garden museum around the materiality of stone and the lightness of a Japanese lantern, the second reduces everything to trash and cyberspace. He treats the museum as a toy store and a site for his retrospective, which is to say much the same thing.

Space Program: Mars could not nearly fill the armory, but its video alone felt as long as a four-hour ritual. And this tea ceremony does nothing half-way. A tearoom? How about three or four different sheds, including an airplane lavatory, all of red-striped wood beams and blue Dow Chemical Sheetrock? Sachs has not just one but two fountains, one an industrial sink with liquid soap and running water, the other more like a backyard pool. Stacked iron stoves mime a pagoda, but with other grills strewn along the way.

These represent male territory, a universe in which women prepare tea while men take over now and then for a barbecue. So does a second room, for used appliances that Peter Fischli and David Weiss would envy. One device promises to dispense alcohol, just as the Upper East Side space program included a bar, here with Stoli bottles relabeled in black marker for less upscale choices. A video of Mount Fuji turns up, and so does a sign in Japanese, but sure enough from Macdonald's. And then a space suit reappears, beside the stairs to the second floor, where Tea Ceremony gives out. So much for higher things.

Sachs does not quite elbow out his predecessor, although this is hardly tea for two. The main event weaves among weightier work by Isamu Noguchi, drawing on its monumentality. The shelves for appliances could almost parallel the long shelf for smaller sculpture upstairs. Sachs has explanations for all this, on plastic cards much like the ones that usually serve as guides to each room. He swears to his own tea practices, and he claims that Japan is taking the lead to Mars, where it will have the first tea ceremony beyond planet earth. The first, that is, unless one counts this one.

Still, it all feels like excuses for more of the same, with Space Program 3.0 set for a global tour just when his pretend boom boxes and, yes, another stocked bar have come to the Brooklyn Museum. Art institutions have a soft spot for Sachs, as the bad-boy artist who can look at home in high places, much as he enlarged plastic toys as summer sculpture for Park Avenue in 2008. So what comes next to Astoria, stuffed animals by Mike Kelley lounging in the garden? Styrofoam rocks by Ryan Trecartin and a fishtank with basketballs by Jeff Koons instead of a pond? Enough with tea. Like Sachs and his guests, I need a real drink.

Science for boys

Between budget cutbacks and Republican ideology, the space program has increasingly fallen to the private sector. As if that were not bad enough, it has fallen to artists. In the process, it has ditched the science and taken on the air of a preadolescent male adventure. It has also shrunk to the scale of the Park Avenue Armory. It is going nowhere fast, but it tries ever so hard to entertain without quite deciding whether to let one in. Houston, we have a problem.

On the good side, it may finally ship Tom Sachs off to Mars. Sachs has staged his "space program" before, its memorabilia visible as "Museums of the Moon" on one way out. If others have given up on a return to the Moon while paying lip service to red planet, though, so has he. Space Program: Mars scatters a forlorn set of props around the vast drill hall, with a space capsule at its center. A crew of thirteen keeps the program going and the art a work in progress, including some odd red shapes on the floor, like Minimalism's moon rocks. Sachs was present, too, on my visit, checking email while doing his best to interact as little as possible.

It this summer's art lost in space? Tomás Saraceno has his own module on the Met's roof, as a glass and steel invitation to the clouds. And art at the Armory has a weakness for entertainment as it is. It has invited one to crawl through balloons and stockings, with Ernesto Neto, and had Peter Greenaway simulate art history's ultimate crowd pleaser, Leonardo's Last Supper. One can enjoy the irony that Leonardo dabbled in science and speculation. Now if only Sachs had something of Saraceno's surfeit of ladders, mirrors, and dreams—or Leonardo's reticence and rigor.

In an art scene with far too many boy toys and macho installations, Sachs numbers among the worst. Four summers ago, he enlarged actual plastic toys to sculpture for Park Avenue, and his new components include a stand for (ahem) "hot nuts" and "ignition." Astronauts need to eat and to take off, but one can hear the artist's desires loud and clear. Robert Irwin serves as an obvious guru to the work's madness, although Irwin's California sensibility truly pushed the limits of perception. As a filmed orientation has it, Sachs wants his team to work hard and to play hard, if maybe not too hard. Do not try too hard either to tell work and play apart.

The ambivalence to visitors starts with the artist's welcome, and so do signs of his outsize ego. Before touring the capsule, one must go to the "indoctrination station." One can also, with enough ingenuity, locate the theater. Does that mean that one should start there? Oh, one can start anywhere, an assistant replied, but do look at the movie. With no idea of its length or its beginning, I felt proud to have lasted through about ten minutes of exhortations to "be on time," "be thorough," and other sage advice.

As it happens, the movie lasts about three quarters of an hour, and the part I saw left me thoroughly unprepared for a single question on the written exam, at the indoctrination station. (Just how full should one leave a dustpan?) Had I done better, I could have faced an oral exam, but I settled for my acquaintance with a NASA flag and hot nuts. I had to trust another assistant, who explained that the two-stage capsule has space for work below, with a bed and (yes) bar above. As the film has it, Sachs and his crew do this "because it's hard." If only they knew.

Folie à deux

One can feel at home for the summer in Socrates Sculpture Park. And for once that has as much to do with the park's name and mission as with free evening movies. For once, too, the most ambitious sculpture in the city's parks is not by sculptors, and it may not be art. Its urban architecture includes Tree Office, a raised platform with free wifi—although people use it more like a tree house, without laptops. It includes striped poles charting a possible future on the way to the Queens waterfront. And, entering their midst a few weeks later, it includes Folly: Curtain, a twenty-five foot shelter, open only to the elements, family, and friends.

With their folly, Jerome Haferd and K. Brandt Knapp invite plenty of associations as well. Both architects, they sound a little bemused when they recall them. Someone wanted to get married there. Someone else hated the thought of marrying in a jail.  I thought first of a greenhouse and then the Crystal Palace, the pavilion that stood in London's Hyde Park from 1851 until 1936—but here without the crystal and without the exaggerated claims of a palace. A New York Crystal Palace lasted only five years after the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in Bryant Park, before burning down, but that was back when people had more faith in the industry of all nations.

I thought first of a greenhouse and then the Crystal Palace, the pavilion that stood in London's Hyde Park from 1851 until 1936—but here without the crystal and without the exaggerated claims of a palace. A New York Crystal Palace lasted only five years after the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in Bryant Park, before burning down, but that was back when people had more faith in the industry of all nations.

Haferd and Knapp sound downright annoyed when asked what this thing is or when hearing that it is art. Their two-part title announces their aim, if maybe a certain ambivalence to go with it. (The park's Web site uses alternately one word or the other.) A folly, they explain, is an architectural fancy without utilitarian function. Granted Saraceno's Cloud City on the Met's roof looks like architecture, but it embraces metaphor. They prefer to speak of systems and structures.

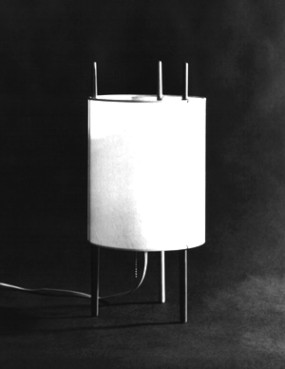

Their folly has plastic chains for walls, some not anchored in the earth so that one can penetrate. In reproduction, they almost dissolve into a shimmering white curtain. They also mark out something like rooms, in quadrants, but with one quadrant displaced to the center of the half facing Astoria. Wood beams hold it all up, while creating gables and at least two peaks. The gazebo's asymmetry becomes more obvious and welcoming the more one circulates. The architects speak of it as porous and transformative.

As for that tree house, by Natalie Jeremijenko, and the poles, by Mary Miss, they have much the same idea. They embody "a vision for Long Island City," as an extension of this spring's show at the Noguchi Museum. Not everyone in "Civic Action" makes it as successfully across the street to the park, but then not everything made much sense in the first place. Even the poles make less sense if one tries to decipher the screens attached and the sounds emanating here and there. These designers are positively bursting with ideas for the community, like it or not. Jeremijenko's AgBags sprout from what would normally hold stage lights or a sound system, while her Greek cross "chars" the grass not far from a "salamander superhighway."

Actual salamanders will have to settle for leftovers from the Saturday farmer's market, and other visitors will have to settle for a less than super walk along Broadway to the N train. Systems are seductive, though, and so are visions. When Haferd and Knapp speak of "twenty-five by twenty-five: and of "four by four," they are speaking, too, about a neighborhood taking shape. They might even be speaking about art. When Immanuel Kant described art as purposiveness without purpose, was he calling it a folly? Maybe not in the same way, but he might still welcome this curtain as art.

Tom Sachs ran at the Isamu Noguchi Museum through July 24, 2016, and at The Brooklyn Museum through August 14, "Space Program: Mars" ran at the Park Avenue Armory through June 17, 2012, "Folly: Curtain" in Socrates Sculpture Park through October 21, and the extension of "Civic Action: A Vision for Long Island City" through August 5. Related reviews look at that last exhibition in full and other 2012 summer sculpture in the parks.