More Real than Realism

John Haberin New York City

Georgia O'Keeffe: Abstraction

Georgia O'Keeffe's abstractions take people by surprise. The Whitney boasts of that in bringing the work together. Pretty much every review begins with it, even if it prefers to reproduce a photograph of her rather than her own art. There is more to O'Keeffe than animal bones bleached in the harsh western sunlight. There is more to a woman artist than flowers—so much more.

Her abstractions show how often she surprised even herself. Instead of sustaining an image, including her image, she pushed an image just to see what it could become. When it got predictable, she threw it away and started over. Is this really an artist known for her purity? O'Keeffe gets one thinking how pure her abstraction or realism ever were. As she said, "Nothing is less real than realism," and it drew her close to abstraction all her life.

The first American Modernism

Frankly, much of the surprise feels stage managed. It has to be. Museums have a job to do, and that includes creating a buzz. Critics have a job to do, too, and that includes reading the press release. A show this strong also sustains the vision of its curators, led by the Barbara Haskell. Starting with her first charcoal abstractions in 1915, in her late twenties, Georgia O'Keeffe was central to establishing modern art in America.

That cow's skull has made an awful lot of posters. Still, if you know the artist just from her posters, go immediately to the back of the class. The Whitney draws freely on the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, where the show makes its final stop. Yet it also includes many paintings on permanent display in New York, where O'Keeffe did so much of her work before heading off for New Mexico. She learned from the city's canyons and skyscrapers, like the Radiator Building on 40th Street, which she painted. She used still life that one can set up in a New York apartment.

She absorbed Modernism early. Born in 1887, she came east to the Art Students League, then dominated by William Merritt Chase and American Impressionism. But she was looking around. In 1907 she caught a show at 291, the avant-garde gallery run by Alfred Stieglitz. At the University of Virginia in 1912, she studied the ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow. She quickly surpassed him.

Dow taught art as a world to itself, with its own elements—in line, mass, and color. However, formalism for him, Arthur Dove, or Oscar Bluemner has nothing to do with Clement Greenberg, Jackson Pollock, and "all-over painting" after World War II. For still others of her time, abstract compositions derive from landscape, and they sit perfectly still like a landscape, too. Their flat, dry colors keep their outlines, and one can see the artists straining to balance their design. From the first, nothing for O'Keeffe lies flat or sits still. Her richly shaded marks flow across and against one another, and her colors glow in the dark of that shading.

Between teaching jobs in the South, she returned to New York in 1916 to complete her certificate at Teacher's College. Her charcoals caught Stieglitz's eye, and she began to exhibit. She experimented in watercolor, pastel, and finally oil. Alfred Stieglitz exhibited her work, and they became lovers. His photographs of her in 1918 and early in their marriage, after 1924, helped make her a legend. For better or worse, they also cemented the link between her work and an erotic charge unlike any in American art.

Starting with her first trip to New Mexico in 1929, she slowly grew apart from New York and abstract painting. This show mostly ends after her hospitalization for major depression in 1933. Yet the work ripples through generations of artists after her. Vaginal imagery from Blue Flower in 1918 bears on feminist art, and so does her willingness to place her own image front and center. Bars and curves of color that bleed into one another anticipate Morris Louis and Helen Frankenthaler in the 1950s—like her 1919 Red and Orange Streak against a green background and a 1924 Red, Yellow, and Black Streak. By the end, her images had become as symmetric and "all-over" as Modernism could ever wish.

The stage manager

If O'Keeffe's image feels stage managed, she deserves credit as stage manager. If her cow's skull has become too much of an icon, she had to know its place in the myth of the American West as a new Eden. She liked to deny that she even liked flowers. As props go, they simply came cheap. She knew perfectly well, though, their association with femininity. She reveled in it, while putting it through its paces.

Her entire life has mythic proportions. She could hardly have a better birthplace than near Sun Prairie, in Wisconsin. She could hardly choose a better place for her summers after Stieglitz died, in 1946, than Ghost Ranch. She valued her independence enough to leave New York in 1908 for commercial work, when a woman faced few choices other than marriage. It says something that, after hooking up with Stieglitz in 1916, she took off again to Texas for two years, for her last teaching job. At her death, she left behind her own museum and study center—with over a thousand of her works.

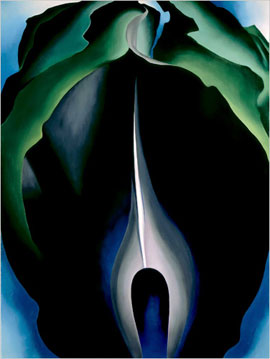

Her nervous breakdown, while on commission for murals for Radio City, shows the pressure she must have felt from her own success. She had a love-hate relationship with her own myth, but both the love and the hate kept her creating. When Stieglitz's photos labeled her an erotic artist, she switched gears—starting with the very switch from charcoal to color. The 1920s introduced more white into her paintings, in a larger and thus more impersonal format. Before long she was basing abstractions on clam shells, far from the softness of flesh. But unyielding ovals that may snap shut have sexual overtones, too, and the flowers were back with Jack in the Pulpit in 1930.

One often hears that Stieglitz exploited her to further his own career. He was over twenty years older and was married when they started their affair. His portraits of her made his own legend as a photographer. Yet he promoted her success, encouraged her to take up oils, and followed her on her trips to the Southwest. He saw his photos as an act of love, and he took three hundred of them over the course of nearly twenty years. She boasted that "nothing like them had come into our world before."

O'Keeffe collaborated with them as an act of self-creation. Long before Cindy Sherman or Hannah Wilke, a woman was shaping and reflecting the male gaze. She poses nude with her hair drawn back from her classic bone structure. Clothed and with her hair down, she massages her breasts and exposes her armpits, as an obvious metonym for pubic hair. She also poses in front of her paintings, and it is hard to know where the backdrop begins. She pretends to fondle the two charcoal black balls like nipples.

The photographs, set apart in a corner room, cross the boundaries between realism and abstraction. They merge the art object and its process of creation. They unsettle the distinction between the artist's image and the art image. Both associate austerity and sensuality. These strange pairings define O'Keeffe's work all by themselves. Taken together, they are another real surprise.

Abstraction as revelation

The Whitney speaks of "Georgia O'Keeffe: Abstraction" rather than O'Keeffe's abstractions. That makes sense. For one thing, only a few works make no reference to realism, such as the charcoals and the very first series in oil. Even the charcoals have those nipples. When she introduced color, in a watercolor of 1917, it looks like a totem in profile, and she subtitles it Portrait of Paul Strand. Besides, abstraction in the singular points not just to an art object, but also to a process.

For O'Keeffe, the process works in both directions. As a photographer, Paul Strand helped give abstraction its old sense of abstracting away from "real life." He pared things down to essentials, and she does just the opposite. She works in series, and the first version is the furthest from life. It is also the furthest from Strand's sense of beauty as elegance. She almost always starts with a set-up, a still life. Then she reimagines the object as an image all her own, before bringing it back to life.

She adds pastels and a splash of watercolor in O'Keeffe drawings, with an impulsiveness I never expected. She lets brushstrokes curve and spread. When she changes media, as in her first oils of 1918, the colors have the sudden intensity of a personal discovery. The rest of the series then progressively tightens and defines the forms. She encounters the objects all over again and comes to know them. Rather than abstraction paring down realism, reality overflows abstraction.

The lack of separation between realism and abstraction shows, too, in her love of shading. Only her late work has anything resembling Greenberg's "flatness." By that time, it has become all but empty of feeling. The show opens with a dull if surprisingly contemporary picture of clouds, from the early 1960s. A view of houses in the 1950s makes them look like airplane windows seen from outside. After so many years of close touch with objects, she has adopted a view from above.

Her best work, right down to the bones and flowers, bring a shocking intimacy from below. Think of her early preference for still life over landscape—for something palpable. In the shock of encounter, she often gives a tabletop the elements of a stage set. Shading on a white suggests a curtain, and a boat's silhouette centers on its sail. In the "portrait" of Strand, the totem's deep primary colors swirl against a pool of yellow light. Night scenes contrast white and yellow in order to capture blackness.

Blackness and open space enter for real between Jack in the Pulpit of 1930 and Black Place of 1944. It may have to do with depression. It may have to do with her need for the isolation of New Mexico. She painted much less in the thirty years before her death in 1986, and her health made her give it up almost entirely after 1972. Still, she found both privacy and revelation, austerity and sensuality. Her whitest image is a flower, her most colorful the indefinite space of abstraction, and her darkest a tent door at night.

"Georgia O'Keeffe: Abstraction" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 17, 2010. A related review looks at O'Keeffe drawings.