A Tale of Two Critics

John Haberin New York City

Action/Abstraction: Pollock, de Kooning, and American Art

Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg

"A good deal of twentieth-century painting," Harold Rosenberg once wrote, "is painting as art criticism." Why, then, not display the criticism?

Thanks in part to Rosenberg, the Jewish Museum can do just that. "Action/Abstraction" provides a brief but intense history of Abstract Expressionism and its aftermath. Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning may never look more explosive, and the simmering split between color-field painting and Pop Art may never look more divisive. However, the exhibition sees them all through the eyes and words of their most famous champions, Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg.

It quotes them on the wall labels, and it displays their articles for all to see. It alternates their holding court on video. More to the point, it plays out their competing positions through the work. Another critic (and a notable contributor to the exhibition catalog), Irving Sandler, catalogued the period as "the triumph of American Painting." This show makes it seem less like the field of victory than a battleground.

Or does it? The show has one looking for what they had in common after all, only starting with the power of words. Has art become a branch of applied philosophy? I can take pleasure in just that, but these two critics had something else in mind.

Order and action

Clement Greenberg did not coin the term Abstract Expressionism. Credit for that goes to Robert Coates in The New Yorker. However, for a time he converted abstraction from a possibility to a necessity, and his formalism has dominated debate ever since, if only as a target. Greenberg demanded that painting be true to itself and to "all that was unique to the nature of its medium." He wanted artists "to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence." When he wrote those words, in the 1963 essay "Modernist Painting," he had moved further than ever from expressionism, to support of what he called post-painterly abstraction.

Rosenberg, writing in 1962, had his own name for art of the 1950s, action painting. He saw the canvas as "an arena for action," with the artist as the combatant—which, of course, makes the critic a warrior, too. His love of process as much as product left him more open to representation than Greenberg was, and even conceptual art could strengthen his case for the artist's intentions. Yet it also left him, like his rival, increasingly afraid for art's future. Greenberg found grounds for hope in painting boiled down to its definition, but Rosenberg came to fear "the de-definition of art." Where once he celebrated the artist's ego and anxiety, in the 1960s and 1970s he grew suspicious of "the anxious object."

From his early writing in Partisan Review and The Nation, Greenberg loved to play judge and jury. He anointed Jackson Pollock the "most important artist of his generation," as if he had himself made it possible, and arguably he had. He understood art as critique, but he also meant it as an affirmation of order. When Willem de Kooning painted de Kooning's Woman I, Greenberg saw an act of betrayal, with high culture at stake. By competing with the Old Masters on their own terms, the female nude, de Kooning had skirted the task at hand—"the use of the characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself." It sounds like a Stalinist's demand for a heretic's self-criticism, although Greenberg despised Stalin and Hitler as reducing culture and humanity to parts in a machine.

Rosenberg liked no one better than de Kooning, and he tuned into the hints of pop culture in Woman before Pop Art even existed. As critic for The New Yorker, he became friends with the magazine's most high-profile cartoonist, Saul Steinberg. And when Philip Guston introduced anxious cartoon images into his art after abstraction, Rosenberg set him alongside Mark Rothko and Arshile Gorky, as dogged survivors in the arena for action. All three, he felt, "underwent a crisis out of which emerged a new artist," as indeed Rothko had in 1949. On video, he responds to whether an action painter can paint slowly. The action, he replies, can take a lifetime.

Long before emerging artists had to attend the right MFA program, Rosenberg saw "the starvation diet of formalism" as assimilating art into the academy. He might have disliked the whole premise of this show, for putting critics on a par with artists. He believed that Frank Stella had put pedagogy ahead of painting. "Artists of the past have said that there are no problems in painting, only solutions. . . . One step further and the paintings can be abandoned for the sake of the problems."

The critics diverged even in how they went out of fashion. Action painting became a textbook curiosity, a cover for male artists with ego to burn. Greenberg, in contrast, remained all too relevant—as the embodiment of Modernism and a powerful reason to reject it. If abstraction really can stand above social and political realities, then it has to go, on both political and esthetic grounds. If painting has an essence, whereas Cindy Sherman or Tracey Moffatt has only selves, then the medium itself deserves to die. So, at any rate, goes the history lesson, from Modernism's triumph to its defeat, as linear and inevitable as Greenberg might desire.

Art and argument

This pocket history of Abstract Expressionist New York still has its power, but does it leave out everything that matters? Maybe so, and the Jewish Museum raises suspicions from the moment one enters. On one screen, it plays the famous film of Jackson Pollock dripping. To its right, de Kooning works patiently on a canvas, his gaze fixed on nothing but the application of color. Why, then, is de Kooning the archetypical action painter and Pollock the disciplined critic? And which of the two drank more quickly at the Cedar Bar?

Questions like these keep returning throughout the show, but a contest of will is already on the agenda, and it does wonders for the paintings. "Action/Abstraction" gives two impressive reasons, right or wrong, that a lot was riding on art. They just happened both to be Jewish New Yorkers, and did they ever like to argue. When the exhibition departs slightly from chronology, it is to make each room the occasion for an argument. The first floor amounts to a tidy survey of Abstract Expressionism, with paintings often paired side by side, one to represent each critic. Upstairs a room apiece for Greenberg and Rosenberg carries the story into the 1960s, as painting once more tries to sort out its future.

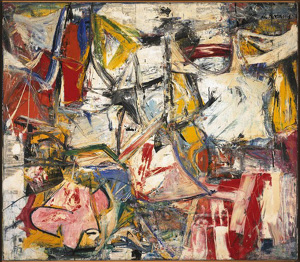

The plot could almost recap West Side Story. In the first room the stars of the rival gangs show off. With Convergence in 1952, Pollock packs more color into an all-over painting than I ever remembered. Meanwhile de Kooning turns from the dense, tiled blacks and whites of Black Friday to the fractured color of Gotham News in 1955. Maybe Pollock and de Kooning took their rivalry half as a joke, especially after a few drinks. (No, you are the greatest artist.) Yet a lot rode on who backed whom.

The second room turns to the teachers, Gorky and Hans Hofmann, who also taught Michael West and Albert Kotin. Lee Krasner met Hofmann at the Arts Student League and introduced him to Pollock. Pollock, in turn, slighted Gorky, but de Kooning found an influence—and a friend. Naturally the critics again took sides, with Greenberg speaking up for Hofmann.

Their choices say a lot, too, about their rival hopes for abstraction. Hofmann taught Cubism and structure. Gorky's stained canvas and dream landscapes introduce a debt to Surrealism as well. By the same token, one can see Greenberg as extending Cubism but disdaining its identification with nature. Rosenberg's action takes up the spontaneity of Surrealism without its mysticism. A photograph reveals the quirky hanging of paintings on free-standing wires in Pollock's first gallery show, at Art of the Future—another reminder of the art's connection to prewar signs and symbols.

As in West Side Story, the action has to take a break for those relegated to the sidelines, especially women and minority groups. A third room gives space to exclusions—Krasner, Grace Hartigan, and an African American painter, Norman Lewis. Another room serves as a kind of comic counterpoint to the primacy of painting, in sculpture by David Smith and others. With Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt, especially in Reinhardt's black paintings, confrontation again comes to a head, as edges harden and colors settle into close tones. Finally, in art after the end of art, the critics pick up the pieces as best they may.

Scanning the playbill

During intermission, one can always scan the playbill. Here that means a splendid array of gallery invitations, reviews in their original magazines, and photographs. Pollock crosses his arms for Life magazine, while a larger group poses as "the Irascibles," part of a protest against a museum exhibition that misses the future. The Salon des Refusés at the birth of modern art sounds humble by comparison—literally castoffs as much as fighters. And the action heroes never stop arguing among themselves. In typewritten letters, Clyfford Still manages to complain to Greenberg about a pan and to Rosenberg about the terms of his praise.

In the end, nothing can stop the argument from breaking out into real divisions. Upstairs in Greenberg's post-painterly abstraction, drips give way to pours, in the hands of first Helen Frankenthaler and then Morris Louis. Rosenberg observes images emerging from the smears of Abstract Expressionism, as with Jasper Johns. Still, it is all over, although Greenberg lived into the 1990s. The show begins in 1940, with Gorky's Garden of Sochi, and it ends with Guston's 1976 conversion to a claustrophobic realism, two year's before Rosenberg's death. Yet the action—or maybe abstraction—belongs almost entirely to a decade in between.

What is one to make of an argument that leads right to its own dissolution? Anyone will come away believing in the restless intellect of two great critics, and yet their own logic ends up undermining the plot. In the years since, the divisions have only multiplied, into pluralism. Maybe history has not been kind to Rosenberg. Yet his anxious catholicity looks downright prescient. The installations in the 2008 Whitney Biennial really do abandon painting for the problems.

Even before the breakup, the show's memorabilia open a wider view than that of the warriors. In magazines, writers debate whether Abstract Expressionism is commie propaganda or the exemplar of American freedoms. A nicely dressed chimp paints on the Today show, a sign of society's disbelief and derision. Those contexts, too, have hardly changed. Postmodern artists and critics have derided American artists as tools in the Cold War. Morley Safer on Sixty Minutes these days still gets to sniff that a three-year old or a thrift shop could produce a Pollock.

For all that, the critics and the art they so admired look better than ever. They can hardly help it. The museum has borrowed classics not often seen in New York, such as four paintings from the Albright-Knox in Buffalo and three of Gorky's greatest. It includes unusual fare when necessary, too. A tan, freely brushed painting by Reinhardt helps with the transition from Pollock to geometry. Krasner turns up with her brightest colors rather than her finer, larger shades of brown, to distinguish her from Pollock—and to underscore the theme of women sidelined by critical bias, like Sonia Gechtoff, and male success.

The rooms help, too, and not just with the souvenirs and critical quotations. They have the smaller scale of the art's first museum displays. This is not the renovated Museum of Modern Art with its fixation on Pollock alone, huge galleries, open sightlines, and walls that never quite touch the floor. At the Jewish Museum, oil paint on canvas positively leaps off the walls, as if to prove Greenberg's notion of the art object dead on. The breasts in Woman resemble closed fists or boxing gloves, and they all but punch one in the face. Abstract painting may never have quite the same punch again.

Hyperbole, provocation, and the ego

As one last payoff, the show looks past its own thesis, willingly or not. From the opening video, one can ask just how much the critics truly differed. At the very least, they had to work awfully hard to maintain the difference. Woman earns Greenberg's displeasure, but the black next to it could almost outline the same woman, as filtered through one of Pollock's favorite paintings, Guernica. Then the drips pull apart to suggest two women flanking a brooding profile, perhaps the artist. Greenberg took all that in stride, as part of the essential "tension" between subject matter and the two dimensions of painting, but Pollock and de Kooning both did their best to make the tension difficult to sustain.

When it comes down to it, the critics are speaking the same language. Both write fluently for a public beyond art magazines. Both act at once as art's champion and its theorist. Both see art as in need of a champion—and for much the same reasons. Where Rosenberg has "the anxious object," Greenberg has "crucial problems," rooted in "the exacerbation of this self-critical tendency." When he wrote that in 1963, in "Modernist Painting," the formalism that he admired faced a whole new crop of challenges from within American art.

Both have a knack for hyperbole. Greenberg sees something "achieved and monumental, beyond facility and taste," while Rosenberg sees "interior life at its highest intensity." Both relish provocation. "All profoundly original art," Greenberg declares, "looks ugly at first." Woman was "a mistake," Rosenberg concedes, but "one may ask whether there is for the artist any other way." In practice, Rosenberg wrote admiringly of Ken Noland, while Greenberg wrote a fine review about Gorky, and they converge theoretically as well.

Greenberg may privilege the art object, but he, too, sees product as inseparable from process. "If the avant-garde imitates the processes of art, kitsch, we now see, imitates its effects." He may seem above anything external to the work, but the choice has political implications, just as when Hitler and Stalin in his eyes chose kitsch. "Where there is an avant-garde," he wrote, "we also find a rear guard." Above all, both see painting as a fecund but individual triumph, and the threats to its future as anxiety about culture. They see it, like their own relationship to Judaism, as secular—as bound to the present moment and the present object in this world.

How many critics does it take to screw up abstract painting? Quite a few, in fact, several of them Jewish, and one can spot them briefly in the memorabilia. The finest of all, Meyer Schapiro, draws on elements of both Greenberg and Rosenberg in articulating "the humanity of abstract painting," but with objections of his own. Painting has "possibilities given in its own medium," but "the limits of an art cannot be set in advance." It involves "the presence of the individual, his spontaneity and the concreteness of his procedure"—but in relation to form and in order to develop a "habit of discrimination" in the everyday. Yet Schapiro, too, articulates an ideal of "the self in its relation to the surrounding world" very much like that of his rivals, and that ideal was about to face fresh scrutiny even in his lifetime.

The scrutiny began with the artists themselves. When Clyfford Still complains, he is complaining that Greenberg and Rosenberg have no sense of a context beyond the individual—no room for the infinite. Postmodernism is more likely consider the context finite, but social, political, confining, and very contested. If two critics once had a glorious argument, soon artists and critics did nothing but argue. Thankfully, they also started to discover their irony in Modernism all along. Thankfully, too, "Action/Abstraction" recalls a time when big egos meant more than art-world celebrities.

"Action/Abstraction: Pollock, de Kooning, and American Art, 1940–1976" ran at The Jewish Museum through September 21, 2008.