More or Less Contemporary

John Haberin New York City

The 2018 New York Art Fairs I

The Armory Show has become more contemporary by dropping the contemporary, but never mind: it has also dropped the modern. Rather than a pier for each, it aims at one huge experience of the glittery state of the art.

It also comes with a plenty of features, to punctuate that experience. Either the booths are for shoppers and the features for lookers, or a savvy marketer knows how to attract attention. More than ever, it is hard to single out artists rather than sales figures. Should I be surprised that it is also getting ever harder to talk about the art? And that might stand for fair week. Once again this year, I take you from the Armory Show to its partner in Volta, its rival in the Art Show,  its challenger in the Independent, and scrappier alternatives in NADA, Spring Break, and Scope. I defer Art on Paper to a report on fairs devoted to a single medium later this spring.

its challenger in the Independent, and scrappier alternatives in NADA, Spring Break, and Scope. I defer Art on Paper to a report on fairs devoted to a single medium later this spring.

Lacking in insights?

Not that the Armory Show lacks for modern artists. It just reduces them to half their former pier—not as the collectible remains of the past century, but as "Insights." Crane Kalman can still pull off Wassily Kandinsky from 1928, while Hollis Taggart makes a respectable run through Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler, and the glory years of American art. David Klein shows Al Held as not just a one-trick pony, with geometric abstraction as the illusion of three dimensions, but every now and then a respectable colorist. Nor does the fair lack entirely for single-artist booths and formidable impressions. Nam June Paik goes to town for Gagosian, while Mary Corse with Kayne Griffin Corcoran flattens Josef Albers by aligning her mammoth rectangles with a painting's edge.

Still, its heart lies elsewhere, in the international array of art. The interchangeable names of the features alone suggest attention getters more than, well, insights. The front half of the modern pier has "Focus," on the theme of technology and the body. One can see the first in Park Hyun-Ki with Hyundai, who mounts TV sets in rock gardens and photographs friends carrying them, with difficulty. One can see the second in photographs by Rashid Rana with Leila Heller or a "Cartesian grid" of clothing by Claire Tabouret with Night. More often, though, they appear indirectly at best, as in a tub of mist by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer with Max Estrella, folds in monochrome paintings by Karin Schneider with Lévy Gorvy, or blood red splashed on big canvases by Hermann Nitsch with Marc Straus.

Still, they are among the best in show. Less so is "Presents," the tame second year of smaller booths for younger galleries. That leaves gallery roster after roster of artists. It also has people talking more about installations set apart from booths, as "Platform." Most stand by the entrances, like carnival barkers. Sarah Cain covers everything but the metal detectors with clouds, windows, and stripes of raw color, knowing that they will soon be gone.

JR sets his photos outside, in the very midst of traffic along the Hudson. Far larger than life, they overlay faces from the Middle East on a line of immigrants from a century before, and they earned advance talk from their site, currency, and the backing of Jeffrey Deitch. That does not make them any more daring. One might gasp instead at an unusually open wall assemblage by Leonardo Drew, weathered horizon lines by Richard Long, or a shimmering pyramid by Tara Donovan. She works in tall, clear vials rather than disposable plastic cups this time out, but then it is a costly fair. What, though, are the alternatives?

Volta never really wanted to be an alternative art fair: it wanted to remake the mainstream. Is it the victim of its success? True, few other fairs insist on its trademark single-artist booths, although the Armory Show's are a high point. Still, Volta's attention to new artists has taken hold, and it, too, has taken hold—on the pier adjacent to the Armory Show, sharing VIP privileges. In place of chaos and chintzy art, it has fallen to boredom and conformity.

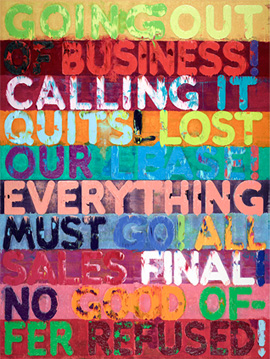

New York dealers have largely departed, leaving mostly second-tier global art cities. It also leaves perfectly decent painting, including abstractions by William Bradley with Unix, schematic landscapes by Tessa Perutz with Pablo's Birthday, string crossing an imaginary city by Kim Schoenstadt with Chimento, and jagged colors emerging from concrete by Troy Simmons with Jan Kossen—but decency can take one only so far. Ironically enough, Volta's high point is now a group show, "The Aesthetics of Matter." With Mickalene Thomas and Racquel Chevremont as curators, that also means black lives matter. Its material character extends to empty clothing from Troy Michie, screen prints on Mylar and fabric by Tomashi Jackson, painted nudes with eyes for flesh by Didier Williams, velvet curtains for Unpacking Sameness by Christie Neptune, a nude ill at home by Devin N. Morris, seeming copies after John Chamberlain by Kennedy Yanko, and African American twists on art history by David Shrobe. Yet Kameelah Janan Rasheed may have the last word on compromise at the art fairs, with posters of Selling My Black Rage to the Highest Bidder.

Major but manageable

The ADAA Art Show is still the classiest March act—now a week ahead of the other fairs, as if to set it more firmly apart. It will never be trendy in the old Park Avenue Armory, but it is keeping up. It encourages single-artist booths, and the exceptions have grown ever-more ingenious in justifying their selection. Who would expect John James Audubon, William Harnett, and Charles Sheeler among claims for "magic realism," with Hirschl & Adler? Diego Rivera in Italy shares a booth with Leonore Carrington, in graphite drawings with Mary-Anne Martin. And if booths for a single artist were not enough, how about one for a single work, a mud-red behemoth by William Tucker with Danese/Corey?

William T. Williams has Michael Rosenfeld to himself for the African American's colorful late work. Its gaps only heighten the grid and the thickness of paint. Mel Bochner with Peter Freeman has irregular polygons slathered with paint and pierced by slashes never quite parallel to the edge, from 1983. Paintings by Tony Smith at Pace illuminate his choices in sculpture.  Jackie Saccoccio recently insisted on her busy paintings as sign systems. Here she returns to a lavish confusion, with van Doren Waxter.

Jackie Saccoccio recently insisted on her busy paintings as sign systems. Here she returns to a lavish confusion, with van Doren Waxter.

Other women include another black artist in Mildred Thompson with Galerie Lelong, nudes by Jane Freilicher with Paul Kasmin, thickly woven paintings by Harmony Hammond with Alexander Gray, mixed media on dark monochrome by Carol Rama at Fergus McCaffrey, and glitter-soaked rags from Lynda Benglis with Cheim & Read. Mary Heilmann adds bright-red furniture to her mix with 303. Janice Biala hung out among all the right people and places, in Paris and Venice. Most often she painted accordingly. Yet her collage from around 1960, with Pavel Zoubok, offers an alternative take on Abstract Expressionism, more grounded in Cubism, like Conrad Marca-Relli. Hers, though, is darker at its core, closer in design to portraiture and still life, and always in motion.

The Independent is still major but manageable, independent but sophisticated. It is the alternative fair for those with little patience for self-styled outsiders. Even its bar would not look out of place in a hotel for the global elite. Yet it takes its aims seriously. It also promotes up-and-coming artists and galleries that share its ambitions. They look great at that, in Tribeca quarters with a view.

Work leans to large painting and small sculpture, like the stubborn elegance of ceramics for Ken Price with Franklin Parrasch—just the thing to make an impact and to move. A theme of this year's fair seems anything but cutting edge as well, East Village art from the 1980s and 1980s. Like much else here, it falls neatly between Modernism's tried and true and emerging artists now. Still, it looks more eclectic than political and conceptual, like Jack Pierson with Cheim & Read or Peter Nagy with Magenta Plains, and it paved the way for others. Other exhibitors include a healthy selection from the Lower East Side as well as Chelsea and Europe. They also run to Harlem for murky abstractions by Carl Ostendarp with Elizabeth Dee, one of the fair's founders, and to Bushwick for Harold Ancart with Clearing.

Ancart paints on paired surfaces, one atop the other like the net on a very modern ping-pong table. They assume a space between painting and sculpture, and many others range across media as well—like Kathleen White with Martos for abstract paintings, small lumpy sculpture, and a chest overflowing with hair. Elisabeth Kley with Canada and Cary Leibowitz with Invisible-Exports both set ceramics in context of wall paintings, while Ruby Neri with David Kordansky makes pitchers like oversexed female bodies. Veils over industrial armature, by Elaine Cameron-Weir with JTT, make beauty a threat. Jane Quick-to-See Smith, with Garth Greenan, adds Native American markers to such collective signs and symbols as a heart and an American flag. They have waited for this since the mid-1990s.

Showing up and showing off

NADA has booths of varied size and price to accommodate everyone, even beyond members of the New Art Dealers Alliance, in its sprawling space west of Soho—with NADA House on Governors Island still to come. Here such Lower East Siders as Nicelle Beauchene, Brennan & Griffin, and Company get to look like prime real estate, while storefront galleries can feel right at home. The two-tier bar makes the fair a comfortable place to hang out for the evening as well. Could I stop long enough to remember anyone? Should I mention clotted abstractions by Matthew Chambers with Marinaro, twisted wood by Lee Relvas with Callicoon, dizzying illusions in new and old media by Zach Nader with Microscope, or post-Cubist colors by Mariah Dekkenga and sexed-up carvings by Jerry the Marble Faun with Situations? But then even an edgy fair caters to shoppers more than lingerers.

Spring Break is exhilarating to the point of utter confusion. How better to stake its claim as an alternative fair? Its old home in the depths of the Farley Post Office left much of it in shadow, and artists responded with work that looked sadly left behind. Starting with last year's move to a Times Square office building, it has cleaned up its act. Not only has the lighting improved, but artists also have to show up for work. They can even afford painting and sculpture along with installations.

Showing up is indeed the key, and so is showing off. Rather than booths, Spring Break has a warren of offices over two high floors, from conference rooms and corridors to dead ends and little more than closets. (If these were actual offices, imagine the fight to claim the most prestigious space.) It takes time, even if it means rushing from one independent curator to another as well. It also comes with a map too small to read rather than labels. Visitors may also never know what they have seen.

Is the fair then a protest against the mainstream, a single outsize performance, or just spring break? One might think the first from signs on behalf of immigration. A mock presidential podium offers a place for announcements or performance art, assuming one can tell the difference. Elsewhere, too, artists could be performing, making work, hoping for clients, or just hanging out. One group busy checking its computers styles itself Amazing Industries, with an unnamed product. No one occupies the bed with a suggestively representational bedspread, and anyway the XX Hotel has "no vacancies."

Art often seems like settings for performance. Coming off the elevators, one sees tense abstraction along with hanging plants. Wall hangings share a room with sound art, gangly orange creatures share a common area with visitors, architectural models blend into photographs of glass architecture, police barricades become mixed-media paintings. Free-standing walls could mark pebbled gardens, an echo of Louise Nevelson and Nevelson's black, or just partitions. People swim past on video, and scales take on a human face when one steps on them. As one series of paintings has it, I Want the Truth, and yet I Want to Be Loved.

Still not satisfied with the alternatives? If you think that the system is rigged, galleries are rigged, and indeed art is rigged, have I got the fair for you—for Scope does its level best to avoid them all. Its striving artists imagine what Jean-Michel Basquiat could have done if he were a white male up on today's fashion, romance, sci-fi, and comic strips. On the way in, I spotted a cartoon girl with her anatomy and teeth laid bare, by Nychos with Mirus. She was hardly the last case of the cutes with a dehumanizing sex appeal. By the time I reached the Wild Horses of Stable Island, my wild ride through the fairs had only just begun.

These New York art fairs ran mostly March 8–11, 2018. Related reviews report on past years, the AIPAD Photography Show, the May art fairs, Condo NY, and a panel discussion of "Art Fairs: An Irresistible Force?" And do not forget the 2019 art fairs, 2020 art fairs, 2021 art fairs, spring 2022 art fairs, fall 2022 art fairs, spring 2023 art fairs, and fall 2023 art fairs to come, including Frieze, Frieze online, Art New York, and NADA.