Left Behind?

John Haberin New York City

The 2023 New York Art Fairs

Spring New York art fairs keep departing, but it takes longer and longer to see what they left behind. More than ever have moved to September, for that first week of the fall season. Yet May fair week now stretches to two weeks, enough to exhaust anyone.

They are a busy two weeks at that. The March fairs are gone for good, as the spring fairs that remain join Frieze in May. They also join what has become a seeming nonstop fair weekend, counting city after city, running year round. Can galleries afford it, and can collectors afford two straight weeks in New York?  If they can, why not use that time to take in the galleries and forget the fairs? My highly selective tour sorts out the competition.

If they can, why not use that time to take in the galleries and forget the fairs? My highly selective tour sorts out the competition.

I have balked in the past at TEFAF (the European Fine Art Fair) for its mix of furniture and jewelry with posh European dealers, but this year it balked at me. I faced a steep price without press credentials. I should have loved to see paintings by Winold Reiss for the art deco interior of a long-departed restaurant, for just one view of the multiplicity of early Modernisms in New York. Instead, I begin with another European import, London's Frieze, now the heart of May's fair weeks. From there, I look at alternative fairs struggling to break through and to the one that does, the Independent. Will it be enough to sustain a future for the fairs?

What money can buy

Sometimes money can buy happiness, and what is an art fair without something to buy? Maybe you heard that Frieze has cut back, to intimacy and restraint, to its vital center. Do not believe it for a minute. Well after the lockdown, it is still at the Shed, the cavernous space living up to its name and the wealth of Hudson Yards. The fair may have just half as many exhibitors as in its first years in New York, but it could easily fit twice as many. Instead, it uses that space to make an impact.

It uses it for features, of course, just as it did back on Randall's Island. An artist has pendant sculpture off the escalators, a nonprofit its time line. Other artists contribute ceramic plates, for sale to benefit the homeless. An installation upstairs, with the "art lounge" and bars, bows to the digital—but in each case the real interest lies elsewhere. More to the point, Frieze uses the Shed for large booths and large work. Its division over four floors just makes them that much less intimidating and easier to navigate.

Sarah Sze (with London's Victoria Miro) demands space for big work, even in painting and not assemblage, as does Georg Baselitz (with London's Thaddaeus Ropac), with not an upside-down person in sight. Suzan Frecon (with David Zwirner) has a solo booth for curved fields of color that push the very edge of a canvas and into the room. Sanford Biggers (with Italy's Massimo De Carlo) could be replying to them all with "soft" painting, but his geometric abstraction built of layered canvas demands space, too. So do Edgar Calel with (Proyectos Ultravioleta in Guatemala City), who brings to painting the same native soil as to his earth room at SculptureCenter, and Sojourner Truth Parsons (with Berlin's Esther Schipper), whose silhouettes translate the flatness of early Modernism into blackness. The "focus" section for younger galleries fits right in, like Tosh Basco (with Company), with the scale and swirls of the glory days of American painting.

They could be adapting their more fashionable installations and body images to the fair market, but sometimes a big display can hold you long enough to change what you knew. Prints of closely spaced photos, by Nan Goldin (with Gagosian), could pass for contact sheets, were it not for their greater size and electric colors. They could pass, too, for the rawness of her great images of sexual desire and human loss. And they still speak of grieving, even as her actors stand tall. They also elude easy stories, with sharp breaks between adjacent settings, indoors and out. This is a brave new world, but bravery is as hard as ever.

The women with Michael Rosenfeld look both back and to the present as well, with work from the year of Roe v. Wade. You expect blunt politics from Nancy Grossman and her zippered heads, but not from textual overlays by Barbara Chase-Riboud. You expect body imagery from Magdalena Abakanowicz, here with a thickly painted surface and slit vagina, and Betye Saar, with a queen of the heavens, but not human eyes from Lee Bontecue. You expect the sheer physicality of sculpture from Louise Nevelson, but what about Claire Falkenstein in jagged copper and a fluid deposit of black glass? What about a turn to black from Alma Thomas in abstraction? Will the alternative fairs offer half as raw an alternative?

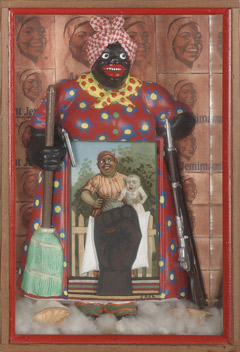

I-54 sure comes close, with a fair for Africa and its legacy. Its former factory in Manhattanville, well to the west in Harlem, barely has space for two dozen galleries, but that just contributes to its rawness. Nor does the selection end in Africa, not when its largest special project goes to Pioneer Works in Brooklyn, for Kenseth Armstead, whose deeply stained wood commemorates stops on the Underground Railroad. It has its echoes of African art, and at least three different artists spread tribal robes against the wall, but also of Baroque royal portraits (for Roméo Mivekonin with Cecile Fakhoury) and René Magritte (in photos by Mous Lamrabat with Loft). Figures by Ronald Hall (with Duane Thomas) move patiently through a surreal landscape that may or may not be the American South. Still, I shall mostly recall the eclecticism and the energy.

Almost an art fair

Salon Zürcher still calls itself a mini-fair, but a group show of eleven women will more than do. Like the gallery, Zürcher, it runs to older artists and abstraction, like the loose grid of Bettina Blohm or the off-kilter one of Victoria Palermo in shiny acrylic. Sonita Singwi laces her drawing with folds and slits, bringing out its making, while Nancy Manter uses Flashe, the rubben-based paint, for the cloudy seas of her Deep Dive. Jo Ann Rothschild turns spareness into density, with stains of every kind framed by simple diagonals. Yet there is space, too, for the tongue-in-cheek play with cigarette boxes and the headlines from Sacha Floch Poliakoff and for Petey Brown, who treats a subway ride as a rite of passage, above rooftops and across bridges. Sue Collier makes the tale of immigrants more crowded and haunting than you ever knew, with black outlines over a weave of colored pencil.

Volta has grown halfway respectable. It has a spacious, central location, the Metropolitan Pavilion east of the West Chelsea galleries. It has few enough galleries to allow one to think, but with a range from New York to the Ivory Coast. True, street scenes of the city look like Sunday painting, and abstract painting gets a bit garish and shapeless. Still, it has nothing like the embarrassment of self-curated artists in many an alternative fair, and even cartoon-influenced art, which is not infrequent, keeps its excess in check. If anything, it might seem as boring as business as usual.

And that, unfortunately, is a problem, in a fair where almost nothing stands out. It starts ambitiously enough, with Basmat Levin (with Ethan Cohen), whose black woman with a covered head looks down from a decorative pattern spanning the walls. Yet even that may not quite add up, and far too many trot out a mildly brushy realism. Booths on the theme of "Fashion Fights Cancer" do not seem to fight for anything, and New York dealers mostly lack a brick-and-mortar space entirely. It is a still a long way from the fair that, years ago, introduced the requirement of single-artist booths, a game changer, and it still seems in search of way to keep up. I hope that next time it finds one.

You may go to NADA for the art, but you stay for the galleries. This fair has not just exhibitors, but members—the kind of dealers that do not hog the spotlight and may not have the cash to try, but keep art creative and alive. While it has grown well beyond New York, you can still recognize many a downtown gallery that you were meaning to see that very day. After a few years in ramshackle housing on Governors Island, it returns to the building that Dia:Chelsea created and where the Independent got its start. With all four floors plus the roof, it can compete for sheer number of exhibitors with Frieze. Now if only you could stay a bit longer for the artists.

Most galleries just show off their roster, which is not negligible. They know how to leave their signature in abstraction, from the light touch and spare imagery of Adrian S. Bará (with Timothy Hawkinson) to the single expanding stains of Per Lunde Jorgensen (with Bonamatic) or larger motifs from several artists (with the Landing and others). As a realist, Joseph Hart (with Halsey McKay) can handle flowers without sentiment. Still, the "special projects" get little more than closets, and others who show a single artist, like Kambel Smith with her sculpted city of landmarks (with Shrine) risks becoming an oversized souvenir shop, much as I wanted to buy in. Sculpture mingling with diners on the roof gets as silly as a charming rat eying pizza boxes in the trash, from Paa Joe (with Superhouse). Not that NADA is, well, nothing, but it feels less like a discovery than like catching up.

So why are self-curated art fairs so awful? After all, New York has no shortage of talent struggling for recognition and representation. I count more than a few as artists I admire and as friends. And Clio has a fine location, a meeting space near Chelsea galleries and only a block from Frieze at the Shed. Yet it looks like a yard sale, with names and paintings packed side by side with neither rhyme nor reason. "An independent fair for independent artists" breaks boundaries only in that the room's architectural divisions give way to chaos. Asking artists pay to exhibit cannot guarantee interest or adventure.

The recent future

The Future is hardly the future. For all its ambitious title, this alternative fair looks like nothing so much as a quiet corner of art's recent past. A reasonable assortment of dealers from America, Canada, and occasionally Europe, it could almost be checking off the boxes. How about geometric abstraction, but with soft edges to entice and not to offend, or portraits that do not shy away from including a charming home and a dog? How about images of strong women, including racers and, with an artist collective called Black Women in Visual Art, just that? Still, these things are in vogue these days for a reason, and booths get clearly demarcated space to show them off in an event space on the northern edge of Chelsea galleries.

Those black woman command one of three "special projects" out front, although these, too, are for galleries—the collective in conjunction with Atlanta's Partnership with Dashboard. Right on the way in, Anna Zorina presents Melanie Delach and Mark Fleuridor, artists with their own space between symbolism and surrealism. Delach frames her compositions with rougher fields of color, to place them further between painting and the decorative arts.  For more women, Laura Berger (with Mama Projects) picks up the trend for flat, full, ghostly nudes. New Yorkers will recognize some decent galleries as well. They may not announce a real alternative, present or future, but they avoid the temptations of tacky newcomers and overblown gallery empires, and that will have to do.

For more women, Laura Berger (with Mama Projects) picks up the trend for flat, full, ghostly nudes. New Yorkers will recognize some decent galleries as well. They may not announce a real alternative, present or future, but they avoid the temptations of tacky newcomers and overblown gallery empires, and that will have to do.

Will I ever give up on the art fairs once and for all? I sure hope so, but even then I may attend just one for pleasure and a bit of self-education. (What else makes art worth your while?) The Independent continues to highlight galleries that gained prominence with an alternative to Chelsea's wealth but have not sold out quite yet. Now twice yearly, with both spring and fall fairs, it returns for spring to its Tribeca space, and the downtown scene will recognize many a name as its own. It is a high-windowed, high-storied space at that.

These are not the monster booths that turn the most prominent fairs into near shopping malls, and many a contributor sticks to one or two artists. One can see its polls almost from the start, with black scrawls by Judith Bernstein (with Paul Kasmin) that challenge abstraction and hypercharged interiors by Elizabeth Schwaiger (with Nicola Vassell) that challenge realism. Fairs all but shun new media in favor of art objects that sell, but crazed photos by Stan VanDerBeek (with Magenta Plains) that nicely complement his early films at the gallery itself (and share the booth with scarier realism, by Chason Matthams, of bodies and the machinery to record their every move). Still, you have to ask, how much can a fair add? As long as you are in Tribeca, could you not just walk right over to Tara Downs for its gallery artists, or Broadway gallery for Edie Fake on a more impressive scale?

A fair can still add something. Charcoal by Emily Nelligan (with Alexandre) may seem a let-down after her solo show last fall, with its landscapes that bring out observation as a process takes time, but it does let in the light. Photos by D'Angelo Lovell Williams (with Higher Pictures) show African Americans in spaces that they can call their own, but the men on pedestals or threesome on a bed are anything but unposed—because a black man is always under heightened scrutiny, especially one with AIDS. Photos by Eleanor Antin (with Richard Saltoun) have not appeared in New York for fifty years. The city then looks ever so spontaneous, ever so populated, and yet ever at risk of dangerously emptying out. Not even this neighborhood will look that way again.

It all comes down to that central question: what are you doing here, at a fair, in the first place? Last year, their return felt like a return to normal after the pandemic, and who could refuse its comfort? One year later, business as usual is no longer as comforting. Maybe next year I can finally call it quits, or maybe this fall. You never know, but maybe you can, too.

These fairs ran the second and third two weeks of May 2023. Related reviews report on past years, the now departed March art fairs, claims for the death of art fairs after Covid-19, and a panel discussion of "Art Fairs: An Irresistible Force?" And do not forget the Armory Show and others in the fall art fairs coming up.