Beyond Pollock I

John Haberin New York City

Lee Krasner in Retrospective

Lee Krasner was a good learner. She always did her homework, adored the teacher, and never forgot a thing. Everyone knew a girl like that back in fourth grade. It has made too many over the years see her, wrongly, as a follower rather than creator. They knew her, if at all, as Jackson Pollock's wife. Yet it also made her Abstract Expressionism's great survivor.

A retrospective in Brooklyn traces her furious independence. It shows her reinventing her art again and again. In its final serenity, it becomes an act of rediscovery and release. In part two of this review, I consider two shows that pair Krasner and Pollock—and how much she gains by the comparison.

After the drip

As a committed ironist, I meant to start with a sexist metaphor, honest, because she would have known it all too well. Little boys hate dutiful little girls but call another boy like that just plain smart. As adults, those same boys are already building their portfolio and getting their picture in the magazines. Her husband himself set that media precedent for art. He also left it to Lee Krasner to handle the guests after his outbursts—not to mention the discomfort and the mess. She could always return to the tiny studio he gave her.

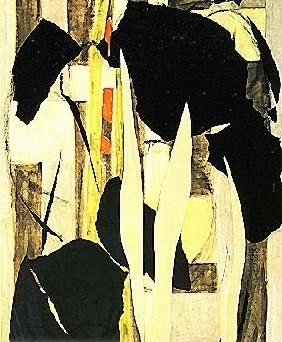

The retrospective offers a chance to see her from far more than his point of view. It shows instead the artist who stood on her own long after his death. It shows the painter who went where Pollock never could, to collage. It shows an artist who a later show has ranked alongside a person of color, Norman Lewis, without either one calling foul. It shows, too, a long series of departures, each haunted by the past. Start with perhaps the toughest of all, the moment of Pollock's death.

For months she felt unable to work. And then came a second death, her mother's, almost before she could begin. It left her an insomniac facing the night, even long after noon. She said later that she could hardly handle color in that darkness. So she took up a brush in a plain brown. And she did so on a scale that she had never attempted before.

The mural dimensions come with the discovery of her own themes—just as they had for the "American century" of Thomas Hart Benton, Mark Rothko and his breakthrough rectangles, or Jackson Pollock himself. For the first time, her titles and broad arcs refer to figures in a landscape. The dimensions signal as well her true entry into Abstract Expressionism. They also show her refusal to let go. She fills every corner, as if determined to leave nothing to chance. At the same time, she rediscovers Pollock's relationship to his art—but now on her own terms.

A brush turns his drips into a fine spray, a final layering over painting's larger outlines. Abstract Expressionism always gives the viewer two scales. It has the fineness of the hand and eye, the huge scale of the body and the sublime. So, too, she draws big with her arm small with what her hand and brush can let loose. Spray infuses a texture of moisture and leafy growth over her big, broader traces of hum figures. Krasner is finding a personal recovery from death, just as her titles often point to rebirth and the seasons.

Squiggles and cycles

Ultimately, Krasner found freedom in what lay right before her eyes. Abstract Expressionism asked art to take its life from its materials. What you see is what you get. Now what she sees is in darkness, as one more constraint on art. And she accepts it, as the dark night through which she has to live. Her brown is the muted color of my dreams.

Brown paint, too, makes one aware of the color and texture of the light brown canvas. It becomes not only a ground for painting but also an element of the work, like the nightmarish brown fur lining Meret Oppenheim's teacup. Krasner never got along half so well with color anyway.

She found freedom in another constraint, too, the space around her. Pollock had lived an artist's life in public. After his death, that fame started to translate into greater financial freedom and a ticket to good galleries. His death also released her from the little room in the house, where she painted small works while he was alive. Out in his larger shed of a studio, her work could explode. Nature, a bare canvas, the studio at night, living on, art itself—they all presented one more wonderful found object.

Krasner always made her greatest progress in the same way—with modest means, a backward glance, love for those near her, and persistence in a sexist world. The combination has often made her hard to see. For many people, too many people, Krasner always tried way too hard, in her art and in her loves. A woman of her time and for today, she has suffered from both her dogged independence and a suspicious deference. Call her the New York School's Hillary Clinton, only home grown, a kid from the city. At least one state art curriculum lists every well-known Abstract Expressionist but her.

She started early, but her work never took off till her husband's death, for all her unchallenged primacy among women in postwar abstraction. And then it offers earthen colors, reassuring themes, and more than a hint of Pollock's final drawings. Titles refer to traditionally feminine associations, in rebirth and the seasons. Dismissive critics have seen her as one more "second-generation" Abstract Expressionist, only older and without the boldness of Michael Goldberg and Sonia Gechtoff—or the delicate, airy beauty of Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler. Stuck in the past, the old formalism of "all-over painting," she thought about every inch of the rectangle. More often than not, what looks like bare canvas holds washes of oil.

Critics may actually prefer that Krasner seem a bit too familiar. If derivative counts as an insult to modernists, postmodernists see right through the "originality of the avant-garde." Robert Hobbs, in the catalog for the retrospective, wants her ahead of her time. In squiggles, he argues, Krasner took Abstract Expressionism as a language, an arbitrary system of signs. In her collages, art lost all pretense of immediate expressionism. It becomes just one more represented object, up there along with all the other totems. Roberta Smith calls her collage a lost chance for greatness in a bland career.

The overachiever

The story sells her painfully short. It writes off nearly thirty years of work, until her death in 1984, as too pretty for its own good. It demeans a smart woman's choices in an era that denied all too many women a chance to choose. It denies the sexism in so much as acknowledging her as the overachiever. Above all, it makes her roots all too distant, by contrasting her with a clichéd image of modernity.

It forgets that, just as Krasner took up squiggles, Pollock and others, too, had been using scrawls and formal design to revel in the arbitrary. A woman, Janet Sobel, may well have invented the technique—or at least learned more quickly. (Do not be too quick either to describe Sobel as an outsider artist.) Hobbs invokes Julia Kristeva, the postmodern psychologist, to put Krasner's scrawls in context of post-structuralism. I mentioned Kristeva myself, in describing Pollock's retrospective just a year ago.

The story overlooks, too, the steady vision in any artist's natural cycles. Krasner returned to collage around 1955, even better than the first time. And then she abandoned the technique once again. She moved naturally between denser drawing and clearing out the undergrowth. Even before her first big paintings, her titles allude to birth and nature. They gave Krasner her first experience of continuing in the face of death.

It misses, too, how she finally cast aside the grid of her sign paintings on the way to gestural abstraction. Abstract art, for all the monolith it speaks of today, could shift its implications in culture and history. Think again of her twin scale. The strips of canvas and paper outline shapes echo and yet swing across the big rectangle of paint. The strips also hold a finer, more private language within, in the delicate oil and charcoal drawings now shorn of immediate coherence.

The strips add texture without, too, in their frayed edges. No doubt a woman would know about life's rough edges. She would know, too, to see fabric as not just surface, but also substance.

Above all, the story associates her with women in Pop Art and beyond, when she really was looking backward, to European Modernism—all the while moving steadily forward. And that is what binds her so strongly to the generation she loved. Brooklyn's choice of barely forty works makes her focus inescapable. Its awkward layout, in which one must go back through earlier rooms in order to exit, actually helps.

Signs and gestures

I want to hold onto Krasner's ambivalence—about her past and about her independence. It defines her creativity so well. Perhaps it makes sense that I shall always associate her big, quiet last paintings with the acid smell of a hair salon, down the hall from the old Robert Miller gallery, in the Fuller Building. I want never to forget that she was a woman among men. I want never to forget, too, the Jew born Leonore Krasner who had no use for religion, the New Yorker in a fast intellectual scene dominated by immigrants, the formally trained artist in a circle all too willing to teach. I want to remember her as all the calmer and more self-assured the longer she sacrificed to others—and the longer others sacrificed her to second-rate status.

If Krasner was exceptional, it was a role that she never craved. Yet she contributes to art even today. One might see that even better if the Brooklyn retrospective had kept fully to chronology. It would have obliged critics to question the discontinuities that they had imagined.

She left an all-woman's art school for Hans Hofmann's classes on Matisse and Picasso, but she never got Picasso's lessons out of her system. She sought out Pollock, but then she cleaned up after him. She had the sharpest mind for theory and the sharpest tongue among budding painters after Barnett Newman, but she shut up once he started talking. She signed her work LK, without taking Pollock's last name, but she kept to initials only, as if unsure whether a woman could ever remain impersonal—and if she should.

Like her hand-lettering, the collage echoes of Cubism suggest a truth in that old show at NYU. She brought to Abstract Expressionism a rigor and a woman's vulnerability to the demands of men, and in turn it gave her gesture, depth, and form. Seen in light of the collage paintings, her earlier lettering foretells the obsessive grid by which critics would long judge her entire generation.

Ann Middleton Wagner takes the initials as a reminder of the simple signs and gestures in her work. All, Wagner argues, served both as revelation and as mask. Krasner articulates the concerns of the artists around her, for all her ambivalence. I think of that vibrant intellectual scene then—how it dictated to artists more than they could stand, even as it also helped them thrive.

Krasner associated her early squiggle paintings with the unreadable Hebrew letters of her childhood. In the same way, artists listened to the tough debates around them and took what they wanted. She herself borrowed a title from a lecture by Meyer Schapiro, without worrying much about the historian's topic, medieval doctrine and a Renaissance painting now at the Cloisters. Like Pollock and the rest, she looked for inspiration to what they imagined as primitive art that turns on the West. For her it was one more discovery in a thoroughly urban art world.

Lee Krasner's retrospective ran through January 21, 2001, at The Brooklyn Museum. Related reviews look at Krasner and Jackson Pollock and Krasner and Normal Lewis.