10.24.25 — Not All Heavy

Nobody goes to see art there anymore. It’s too crowded. New Yorkers know the routine by now, even those among us who cannot aspire to its privileges.

I am still agonizing over the fate of East Village art from the 1980s, Williamsburg, Bushwick, and Dumbo. Thirty years after Soho galleries left for West Chelsea, I am still trying to know what to make of it. It has not kept David Zwirner from hiding to the unwary in Tribeca as simply 52 Walker.

Many galleries welcome in September with the fall art fairs, meaning mostly two things at once and two expenses. They have to do so, just to be seen. They bring with them as much as they can of the past as well. That, too, to be seen. Jordan Nassar indulges in both tiling and weaving with an eye to Byzantium,  at James Cohan through October 4. I could complain, but it is nothing if not suitably traditional. When Tribeca, too, is reverential like this, you know art has gained in confidence or lost in courage.

at James Cohan through October 4. I could complain, but it is nothing if not suitably traditional. When Tribeca, too, is reverential like this, you know art has gained in confidence or lost in courage.

More subtly, Tribeca has taken over the first half of a downtown gallery guide and then some. It took all of this and then some to maintain and to expand the guide after its creator died and galleries hit the road once more. A Lower East Side guide could not last on its own. But now the downtown guide has relegated the Lower East Side to its smaller, second half. Could that be why, as if to moderate the trend, shows in the guide look awfully familiar? Or could art just be settling in?

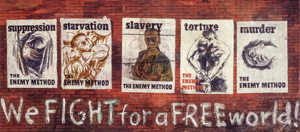

Hank Willis Thomas is acting less as a “New Black Heavy” than a heavyweight African American, at Jack Shainman through November 1, and I work this together with an earlier report this year on Jack Whitten at MoMA as a longer review and my latest upload. You may remember Thomas from a wave of artists sixteen years ago, but now his gallery has taken over an entire building of note further downtown—a weighty stone bearer of official wisdom and corruption barely a block from City Hall. Visitors take an elevator or a grand stair just to see it, feeling only the privilege of art’s inner sanctums. As for the artist, true New Yorkers can take that in stride. He, in turn, privileges them. Both by now deserve it.

Everything for Thomas is a smart twist on race, class, and history, and it may be hard to believe that his latest show is entirely recent and new. Just do let it knock you off your stride too easily or too hard. As the show’s title says, “I Am Many”—or, as a canvas has it, in white block letters, EVERYTHING. He does not quite paint everything at once of course. Starting at the entrance desk, his familiar imagery of hands sets the stage sculptural black and white.  Will one nurture or betray the other?

Will one nurture or betray the other?

Some work brings faces, messages, or something more elusive. Are these sculptures dangerous devices or sources of power? Other work, a stripe or a maze, present a color-field painting. It may or may not pull him back from race to supposed universals in the wake of Frank Stella and Jasper Johns, territorial boundaries and a mitred maze. Perhaps identity itself for a black male is a maze. Like the building, it pulls him into history.

I had a chance to recover a special New York, but would it come to me? Has Thomas sought safe ground in which any race can appear? Like Walt Whitman, does he contain multitudes? Does any proper artist? A flag hangs at rest in one photo, as in an old-fashioned classroom. A neon sign blinks between LOVE RULES and OVER RULES. It could still be trying to define what the choice means to Trump’s America.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.