Get Real

John Haberin New York City

The 2024 Whitney Biennial

You may not receive a warm welcome to the 2024 Whitney Biennial, but you could hardly encounter a more impressive one. You could drive a truck through the entrance to each of its two main floors, at the Whitney through August 11. Maybe you should for self-protection.

Painted clouds frame one entrance, as if the biennial itself had descended from the sky. It opens onto a wall-sized video and unknown voices over gentle music. The other dares you to enter a room of searing yellow. If it all feels slightly unreal, it is, as the show's title has it, "Even Better Than the Real Thing." Yet it seems determined to "get real," with an outsize display of raw materials and all too serious politics. Such, it announces, is the larger than life state of the art.

Losing objectivity

This biennial is thinking big. It has not just the museum's two largest floors, including both terraces, but also the lobby and the space outside the education department and theater. They, too, have lost their intimacy. Entering the lobby gallery is like entering New York itself, with a shopping cart, a fire hydrant on its side, and other debris, although Ser Serpas herself has left the city for LA. If steel spheres framed by piled fencing look like spaceships, welcome to the known universe. Two floors up, Pippa Garner papers the walls with hundreds of pretend advertisements for her own inventions.

Any biennial is daunting, much like the art fairs or a month in the galleries. Take dozens of artists with a work apiece and call it art now, a formula that suits El Museo del Barrio coming up for its La Trienal 2024. Do not even try to keep up with the latest thing, lest one lose one's objectivity, and the 2015 Biennial had a median age of past fifty. Always bear in mind the rediscovery of painting in the new century. This time, though, the Whitney is all over the map. The curators, Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli with Min Sun Jeon and Beatriz Cifuentes, refuse the whole idea of objectivity.

They speak instead of the "permeability" of relationships, the "fluidity" of identity, and the "precariousness of the natural and constructed worlds." They evoke AI as better than the real thing. In practice, the sole AI art is in another show entirely—of Harold Cohen a floor above. The closest thing here looks like characters from a bad superhero movie, in a familiar cross between a robot's armor and winter parkas. Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst claim only to be training the data behind artificial intelligence. It has a lot to learn.

Still, the 2024 Biennial speaks more of certainty than fluidity, and its welcome is precarious at that. Garner's ads, the Whitney swears, dismantle marketing and gender. That huge video past the clouds, by Tourmaline, celebrates a trans black activist and performance artist. Between the yellow walls, the artist, P. Staff, appears in silhouette in ominous black. An electrically charged orange mesh protects the ceiling. And here you thought you could ascend to the clouds.

Already you know what to expect. Nothing will be clear, and everything will be political, if only you could say why and how. The artist will always be present, especially in absence, as with body casts by Jes Fan or bathroom cabinets from Carolyn Lazard filled with petroleum jelly. New media and performance will dominate, from music to dance video by Ligia Lewis that leaves the dancers as ghosts. Thanks to Holland Andrews, freight elevator and stairwell leading up are awash in sound. Here at last is the biennial's promised "dissonant chorus."

Almost anyone and anything can count as American art and add to its vitality. Lewis, who lives in Germany, is from the Dominican Republic, Staff from the UK. Everything verges, too, on art-world platitudes, but with a twist: art here is material and big. That industrial orange curtain has its echo in a descending sheet of smoked glass from Charisse Pearlina Weston. Either might shatter as it falls—and not without a threat to you.

Go with the flow

Most of the seventy-one contributors have a room to themselves. It gives them space like a solo exhibition, yet it also turns almost everything into an installation. Rooms to the side for new media punctuate the flow. Isaac Julien begins his first video since a tale of Frederick Douglass with a wall of mirrors, before a quiet narrative set on several screens. It tracks a silent conversation between past and present American sculpture and an intellectual founder of the Harlem Renaissance. One might have wandered into a maze, where the only way out is to sit still.

Speaking of permeability, they also bleed into one another. Each floor of the 2022 Biennial had its own character. This one has instead a continuous flow.  One can step from Suzanne Jackson, whose layered paint and gel become their own armature, to a different kind of hanging, by ektor garcia in cotton and lace. It is only a step from there to tatami mats and film stained with color by Lotus L. Kang, like Mark Rothko set free from the walls. Karyn Olivier leaves more clothing in a circle on the floor, as a pile of trash or a place of rest.

One can step from Suzanne Jackson, whose layered paint and gel become their own armature, to a different kind of hanging, by ektor garcia in cotton and lace. It is only a step from there to tatami mats and film stained with color by Lotus L. Kang, like Mark Rothko set free from the walls. Karyn Olivier leaves more clothing in a circle on the floor, as a pile of trash or a place of rest.

One might turn from testimonies to abortion by Carmen Winant, more than twenty-five hundred of them, to pregnancy and motherhood for Julia Phillips. You may remember her ceramic hips when you come to body casts from Jes Fan or a bronze liver from K. R. M. Mooney. Nor is it far from Westin's smoked glass to a Lakota tent from Cannupa Hanska Luger—it, too, inverted and suspended overhead. It is a Transportable Intergenerational Protection Infrastructure, because the entire "world is upside down"—while his bison coming up with summer sculpture in City Hall Park is barely alive Draped pillars from Dala Nasser in Lebanon stand beside four Daughters from Rose B. Simpson in New Mexico. They could be a single cross-cultural installation.

Out on a terrace, Torkwase Dyson arranges massive geometry in black as a "playground." Tony Smith and Minimalism meet African American art now. A floor above, Kiyan Williams fashions a reproduction of the White House from black soil. It tilts badly, just as Luger's tipi is inverted. A wall of amber from Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio stands just inside. I mistook them for work of the same artist.

Old media like painting and drawing are rare but worth regarding. Mary Lucier marks a calendar with the many deaths of colleagues and friends. Phillips recovers memory from "conception drawings" in vegetable oil and oil pastel. Mavis Pusey in 1970 took her active geometry from an ever-changing New York, but it looks more like prewar abstraction. Mary Lovelace O'Neal may have been thinking of blackness, but she rides a blue whale in wave upon wave of paint. Jackson is still very much a painter.

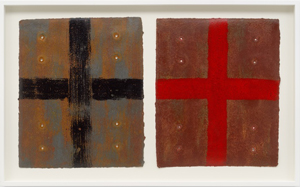

If you forget that, you have bought into a stunning but heavy-handed biennial. It has older artists, like Lucier, Jackson, and Harmony Hammond, all born in 1944, and Lovelace O'Neal, born in 1942, although a generation or two goes largely missing along the way. Hammond, too, works between weaving and abstraction, like Minimalism brought to feminist life. Pusey, like Jackson a black artist, died in 2018. You might not know it, though, in a show that wants desperately to be current. Oh, and did I mention politics?

Music and light

Not that politics is anything new to a biennial, and neither is controversy. The 2000 Biennial targeted Rudy Giuliani, who took his usual potshots at art in return. Artists walked out of the 2019 Biennial over a board member's role in the arms industry and protested the 2017 Whitney Biennial over a rendering of the death of Emmett Till. Politics is news, by definition, but can diversity still make the headlines? Can it take a stand on the fluid and permeable without sinking? If so, does that make it "same old, same old" after all?

Some have thought so, while others have found the biennial's quality at odds with its message. I can sympathize. Many works do hector, like a screed on colonialism from Demian DinéYazhi' in neon. Others may refuse to hector, but wall text does not. There the work takes a back seat to its supposed origins in the issues of the day. That can make art needlessly obscure, but it makes all the clearer how much art conveys issues of the heart.

Artists, then, can still win out. The biennial can take credit, too, for extending diversity in American art from blacks and women to LGBT+ and other nations. That expansion is at its best in video that refuses to lecture, like Julien's. Clarissa Tossin connects Mayan artifacts to life in Guatemala today, while Seba Calfuqueo sees Chile's heartland as if for the first time. They may come down to little more than travel ads, but have a nice trip. Dora Budor lends New York's most exclusive and abhorrent real estate deal, the Hudson Yards, a spooky appeal.

Others are shriller and less coherent. Sharon Hayes tapes classroom discussions (about gender), but they look more like episodes of The View. Lewis listens to church bells in Italy and hears only the dominance of Western civilization. I can feel the puzzlement and pain as Diane Severin Nguyen grapples with war crimes, but only if I get past her ham acting. Still, the impact of video points to what could be the biennial's greatest achievement. It takes light, sound, multimedia, and collaboration seriously.

JJJJJerome Ellis has a lot of J's and an open invitation to respond to the entire biennial in sound, while Andrews already fills the stairs with choral music somewhere between speech and song. Nikita Gale lends a piano without strings her lively Tempo Rubato (Stolen Time). She adopts a literal translation of the musical term for loose, expressive rhythm, but then in this life time is always short. Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich honors a Caribbean philosopher of "Négritude" with nothing more than slowly brightening and dimming light. When she calls it Too Bright to See, she could be speaking of race, philosophy, or the cycle of day and night. Like James Turrell with natural and artificial light, she is teaching herself and others to look.

Too much else is business as usual or, worse, a loaded agenda. Too much, too, is out of the picture. Diversity is important, but it is not everything. The last few years of controversy, classics, and creative hanging are looking better all the time. Still, there may never be a balanced biennial, and there never should be. For now, there is more than enough light to see.

The 2024 Whitney Biennial at The Whitney Museum of American Art through August 11, 2024. Other reviews look back to the 1993 Biennial, 1997 Biennial, 2000 Biennial, 2002 Biennial, 2004 Biennial, 2006 Biennial, 2008 Biennial, 2010 Biennial, 2012 Biennial, 2014 Biennial, 2017 Biennial, 2019 Biennial, and 2022 Biennial.