Bait and Switch

John Haberin New York City

Richard Serra: Switch and Rolled and Forged

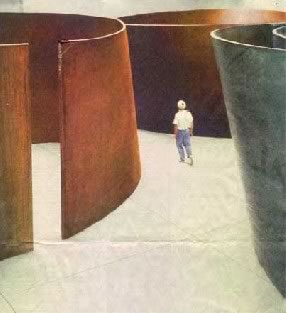

Before anything else, I saw four long sheets of rusted steel. One faces them edge on, curving away without visible end. They lean toward and away from each other, as if considering which way to sway first. In fact, two swing off in near parallel just slightly to the left, two just off to the right. But at first one sees only thick, roughly cut edges. One has to discover the rest for oneself.

With Switch, Richard Serra's mammoth sculpture of winter 2000, the strangest discovery of all may be Minimalism forty years later. What happens as the artist rediscovers sculpture himself, in an era of ironic, backward glances? He has brought a much older sculpture's raw materials, physical weight, and personal associations to a world that Minimalism had discovered, a world at once ordinary, private, and high theater. I also bring the story up to date for 2003 and, in a postscript, for 2006, with the more transparently public theater of Rolled and Forged.

A call to arms

From the moment I saw them, Serra's steel sheets had become an extension of me. As they curve away from one's body and line of sight, they could be one's own outstretched arms. They could be drawing some madcap version of reverse perspective lines in optics class. They could be echoing, or parodying, Rosalind E. Krauss on Minimalism as "sculpture in an expanded field." They could be revising Anish Kapoor, without the illusions.

They make quite literal Modernism's assault on tradition, from one-point perspective to the formalist's obsession with ideals. When Hal Foster wrote about Serra's early work, such as One Ton Prop, he argued that the burst cube could be mocking Plato himself. Now his mockery has made it at least from the Greeks to the Enlightenment. In Japan with the movement called Mono-ha, Lee Ufan could not make steel do more.

Somehow the gigantic masses stand on end, thanks to gravity alone. From the first, Serra has done without external support. In his Prop Piece series, a heavy steel plate stood against the wall, held there by only a thick rod like one that Bill Bollinger might have balanced, catty-corner to plate and ground. One Ton Prop stood much like its subtitle, House of Cards.

Why should sculpture not take care of itself? Minimalism had always just been there, like Carl Andre and his floor tiles. They make me giggle each time I see a heavy sculpture all bloated up or bolted to the ground. When the art comes with the pretensions to play of Alexander Calder, Calder's Circus, or Daniel Buren's pretence of seeing through it all, my giggle may even turn to a sneer. Not here.

I could not sneer at my own outstretched arms or the uncertain path ahead. I could not feel too confident either where I might end up. With Serra's Switch and other late works, something really has changed in Minimalism. It has not become old-fashioned sculpture, but it has taken on a life of its own. It connects the insistently sculptural to painting and to theater.

One looks up to the rusted surfaces as to a star—tall, dark, and handsome. This is going to be terrifying, and this is going to be fun.

The circus animal's desertion

One relates to these sheets as part of ordinary space, but unlike the real surroundings of any other Minimalist. Serra had long asked that one relinquish a bit of one's control over things. Tilted Arc, his most infamous commission, imposed itself even on blue-collar workers used to dealing with weights. They wanted their plaza back, near New York's City Hall, and they got it. By 2000, the work had vanished—destroyed forever.

Now, however, Serra finds new ways to demand surrender, without even a loaded gun. I have walked on Andre's floor tiles. I have put them back with my own hands after someone else has mistakenly kicked them away. I could never touch Serra's eroded surfaces before. The museum could never let me. I would never, ever dare.

At last, Serra's sheets delight as well as threaten. The threat has become part of a roller-coaster ride. Their defiance of gravity seems more a dance of lightness than a precarious balance. Serra's stumbling elephant has gotten off the shelf above me. He has come fully to the ground. He has become almost human.

Perhaps the defeat of Tilted Arc did him some good, but the changed stance came a few years before, in the late 1990s, with the Torqued Ellipses. Now, with Switch, Serra has applied the new relation to a viewer to entirely open layers. The slow curve suffices. I felt like a child folding paper models—or an architect. I felt like a grownup leaving my Valentine's card half open, so that it can sit close by on the bedroom dresser.

Already, from the gallery's entrance, the initial edge-on view undercuts this incredible mass. Parallel layers help, too, suggesting some kind of mutual support, making them seem less likely to fall.

By now, too, Serra's trick has simply grown familiar, a comforting part of the art world. Now, too, it is contained in an immense, pricey gallery, not reducing a public square. Besides, a New Yorker who feared losing open space to Tilted Arc should know better by now. After manipulating the issue of public funding for personal political gain, the mayor has bulldozed enough community gardens. Police barricades wall off space in front of City Hall. I, for once, am heading indoors elsewhere, to look at art.

Lightness and epic theater

As huge as they are, one wants to keep these sheets in sight, to walk along them. Before trying to cut in between those two pairs one first sees, one picks a direction, left or right, and walks beside a sheet. One needs to get a true sense of its scope and weight. Gagosian's outrageous warehouse space leaves enough room to each side for a good handball game, if only one could anticipate the rough bounces off these walls. (A later Serra even allows for zigzags.)

Still, this single, huge work fills the high-ceilinged gallery amply enough. Imagine finding space one day for for four of them! One focuses on it happily. One just has to touch it, to pet the elephant.

Walking by the sheets, if not quite on them, means putting off a good thing—entering between them. One gets to that action before one grasps the whole shape, the entire form. The work really consists of six sheets. Its three pairs form roughly an equilateral triangle with the sides bowed gently in. Thirty years after the broken cube, Plato still takes his lumps.

Plato keeps on taking them once one gets inside, where the arcs tilt more strangely than ever. They make the central space less a comforting enclave than just another spot along a curved trajectory. One moves through that space like through the park on warmer weekends. As in Central Park, too, plenty of others are moving alongside. The joint is packed.

First, though, one has to follow that narrow slot between any pair of sheets. Out the other side, one could be back where one started. Looking back, too, from another of the triangle's three corners, one starts to seek differences in the curvatures. The differences between parallel sheets, so accidental and arbitrary, tell only part of the story.

Structuralists talked about how meaning, even the mind, emerges from difference, from the inflections in speech to the nuances of a poet. From the same idea, deconstruction made a marvelous mess of meaning. Here the arbitrary differences add up to confusion and theater, but also an appreciation of something else. They connect private experience to a strangely real public world.

Minimalism of the museum

The pairings and parallel tracks of Switch, with their sensation of ceaseless motion, make me think of a railway switch. The combined sensuality and threat recall the teasing end of a whip. The discovery of its form comes with the electric jolt of a light switch.

Serra has not abandoned his own obsessions. He bases the curved sheets, like Torqued Ellipses, on conic sections. The reduplicated triangle likewise suggests a geometrician's rule. It returns one to Minimalism's origins. As with Sol LeWitt, any rule driven to extremes approaches chaos. Foster again captured things for the school's first generation:

In this transformation the viewer, refused the safe, sovereign space of formal art, is cast back on the here and now; and rather than scan the surface of a work for a topographical mapping of the properties of its medium, he or she is prompted to explore the perceptual consequences of a particular intervention in a given site.

There is another kind of switch, however. Think of bait and switch. In the Minimalist equation, Serra has found room for illusion—the illusion of the human amid the postmodern behemoth. A twelve-ton equilateral triangle has turned itself into something between a man, a mobile, and a maze.

With his huge installations, Serra comes the closest of his career to traditional sculpture. By exceeding a Minimalist's human scale, he denies one the chance to interact with a work as its equal. In sheer cost and popularity, it has entered art of the museums and sculpture parks. His sculpture, though, becomes something far from traditional. It is less a shaper of the viewer's space than a shared presence—shared with one's own body and shared, too, among many viewers at a gallery. All cope with the perceptual chaos.

A statue's humanity amounted to a represented one—and an unattainable ideal at that. It meant the general, the public figure. Now art achieves the illusion of the human presence by a very different approach. Poised between Minimalist abstraction and Baroque theater, it creates a communal space among its viewers, drawing them in together.

Self-appropriation

Oddly enough, given Serra's still-macho, gestural style, I might connect the approach to a woman. I mean Maya Lin and her literally groundbreaking work of public sculpture, the Vietnam War Memorial. The influences run both ways. One can see anticipations decades ago as well, in Running Fence, by Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

Serra is not alone. Another older, successful artist is evolving in much the same way. After his endless lectures about purity, Frank Stella pushed his early axiomatic approach so far that The Marriage of Reason and Squalor collapsed long ago. Like Serra, too, that means physical collapse, not the residue of idealism in a LeWitt or with Stella's own Protractors. For Stella's 2003 show, someone could have crashed a car in the middle of a painting by Jean Dubuffet.

An act of rediscovery marks a gesture of appropriation, and Serra has even appropriated himself. His mix of old-fashioned rigor and high theater parallel the flashier appropriations of the Britpack these days. Both look back at a generation when art was first distancing itself from high Modernism, which itself played with reality. And it gets even better three years after Switch, in 2003.

Sure, Serra loves to take on weight. Depending on the installation and sheer number of gallery visitors, from the isolation of Dia:Beacon to a weekend in Chelsea, the same work can seem controlling, contemplative, or open to free play. His 2003 variations on a theme manage all these at once. One has the elegance, mass, and pressure of his earlier ship hulls, but with ample room for visitors to circulate. Another invites the long line of gallery-goers into a maze, only to trap them in its jagged turns. Another, a mere square of plates on the floor, jiggles humbly as it lets one walk on it, while directing one's experience of the floor with its tilt.

Imagine a rule. Distance from reality stands for Modernism. Distance from distance in turn stands for irony and appropriation, the art of ten year's ago. And distance from distance from distance becomes an acceptance of differences and pleasure in the physical world. It may be the art of today.

Once Serra's prop pieces seemed scary because they demanded that the viewer enter, but as an other. That steel rod in a Prop Piece made me imagine a penis already violently cut off, and what did that imply for the viewer? Now the human imagery is gone, along with a nasty, hidden assumption—the male audience. Now steel is more obviously stable and secure, but the work of art has become more fragile and far more real. It has accepted amazement.

A postscript: softening up

When did Richard Serra get so user friendly, even before Serra's retrospective? Six years after Switch, in 2006, even his rolled steel seems to have become soft. It invites one to linger a long time—long enough to appreciate the interplay between mass and vision.

For me, Serra's soft side came with a shock, back when I first saw a child running wild through a Torqued Ellipse. Maybe it came again at Dia:Beacon, where I could not stop myself from exploring four of them. They drew me in, even when I felt trapped, even when the wall seemed to bear down on my shoulders, and even when I knew I might reach only a dead end. It came, too, when I saw two parallel walls on the Princeton campus—appropriately enough, just north of the physics building. Neither bears down on anyone, and a college friend just muttered at the warm, rusted surface: it needs a paint job.

He might not feel that way at Gagosian. As the exhibition title suggests, "Rolled and Forged" pays particular attention to the materials and their texture. It comes as an added surprise that along with four new works Round, a massive cylinder, dates from nine years ago. A darker brown than ever, the surfaces have gone past color and abrasion to something three dimensional in their own right. The sphere even reminded me of a big spherical mud pie this past winter by Roxy Paine. One wants to touch them all, to feel the peeling, encrusted layers of iron oxides.

Of course, one cannot, and that realization comes with the work, too. Serra is always drawing one in and scaring one away. He is always bringing together sculpture and viewer as twin, physical bodies, while then turning one toward the surrounding space. Minimalism had its object makers, like Tony Smith and Donald Judd, and its set designers, like Dan Flavin and Carl Andre. Or rather, pretty much everyone lived in the space between these descriptions, but no one more aggressively than Serra.

In a literal sense, he never grew soft: he started out that way, with early rooms of torn, scattered rubber, where a scatter piece by Carl Andre ran to ball bearings. However, unlike the sphere, the newer pieces never try to stand in one's way. They may even pass as wheelchair accessible. Two dark sheets of different heights cling to a long, narrow chamber's facing walls. Other vertical sheets press against one another, so that the object's top rises and falls like a wave, or volumes sit nearby in utter discreteness, and yet they may start as identical blocks, differing only in orientation. In the largest 2006 assemblage, walls of varied heights and lengths divide a room like checkout counter aisles or the world's easiest maze, and who cares if cash registers do not appear at the end to take debit cards?

Note the openness to sight: these walls, which rise roughly to one's waist, disguise the flow of the space but without obviously imposing on one's view, no more than Torkwase Dyson, who shows Serra's relevance to a black woman artist today. The two sheets clinging to gallery walls disguise nothing but their nature. One looks a second time to see whether they have thickness or merely the optical depth of abstract painting directly on a wall. Serra keeps structuring one's experience through mass and illusion, but this time he wants you up close and not chased away. I miss the wildness and terror of earlier work, but somehow such heavy, inanimate objects still stay one step ahead of me.

"Richard Serra: Switch" ran through February 26, 2000, at Gagosian, in the Chelsea gallery. His 2003 show ran there through October 25 of that year. The work discussed in the postscript, "Rolled and Forged," ran through August 11, 2006. I also allude to two new works by Frank Stella, in a show the month before "Switch" at Sperone Westwater, and I quote Hal Foster's The Return of the Real (MIT Press: An October Book, 1996). I continue this story with reviews of a Richard Serra retrospective in 2007 and Serra drawings and late work in 2011 and 2013.