America at the Crossroads

John Haberin New York City

Crossroads of the World: Caribbean Art

In 1780 a Roman visitor to the Americas found his ideal family. Not that Agostino Brunias labeled them that, but for a classicist truth to nature lay not in chance impression, but the typical—and the typical lay in a glimpse of the ideal. And the ideal came with a lot of assumptions.

The two-child family in his small painting might fit quite well on TV north of the border in the 1950s, except that this one stands mostly naked. They are Caribbean, at a time when Carib denoted the Lesser Antilles, seen as a savage land. It is also led to the word cannibal (and to Caliban in The Tempest). In other words, this family (unlike, perhaps, you) has all the right virtues—enough to make Wilfredo García Domenech's twentieth-century laborer, obliged to extract the Dominican Republic's resources in gold, downright startling on the same museum wall. And he, in turn, makes Olga de Amaral's stiff tapestry painted gold that much finer a commentary on both the past and art. In the Caribbean, as in humankind after the fall, nature must give way to labor and to art.

Brunias painted plantation owners as well as noble savages, not to mention soldiers intent on "pacification," as a very different ideal, and El Museo del Barrio continues with a brutal taste of the slave trade's real gold. Nari Ward covers a baseball bat with cotton, nails, and medical tape, while a nearby display case contains an actual club, a gun, and a snuff box looking ever so much like a gold ingot. "Caribbean: Crossroads of the World" has many stories to tell, and they both are and are not pretty. They are also a mess. I must have seen some two-hundred fifty works just that day (yikes)—with more to come at the Queens Museum of Art and at the Studio Museum in Harlem. This is less an exhibition than a celebration, less a celebration than an encyclopedia, and less an encyclopedia than an excuse.

Convergences and tensions

It is not a bad excuse at that, after ten solid years of research and preparation. In the abstract, the exhibition makes no sense at all. As Latin American art with what a later show will call "An Emphasis on Resistance" and another its "Chosen Memories," it hardly differs from El Museo del Barrio's very mission as articulated by a founder, Raphael Montañez Ortiz, and its sprawl makes that mission harder than ever to justify or to pin down. It can hardly cover in full five hundred artists and four hundred years of the Americas, and it hides the Colombia of death squads and drug wars of Juan Manuel Echavarría. It cannot turn middling artists into world shakers—or salvage ethnic pride with the comforting blanket of creole. Yet it succeeds at recovering the Americas and giving indigenous American art its history.

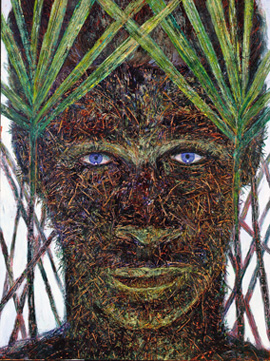

How to begin? El Museo del Barrio starts with a Cuban's own ideal landscape, not by Belkis Ayón or Teresita Fernández in the recent past, but by Estaban Chartrand in 1877, at a time when Europe would surely have imposed on the green of earth. Then comes the very face of the Caribbean, in Arnaldo Roche Rabell's 1986 We Have to Dream in Blue, a young man formed of grass and thorns. From there one has to work hard to find what story to tell—but so, the show reveals, have artists. "Crossroads of the World" cannot have separate rooms for European visitors and natives, without missing the convergences and tensions, but it cannot proceed chronologically either, without becoming a lesson plan. Instead it has six themes, two per museum, each on how views of the Americas converge and collide.

El Museo del Barrio has themes for commodities and culture. "Counterpoints" dwells on the plantation system, while "Patriot Acts" refers to the creation of a Caribbean art and identity. The very idea of a nation state carries European assumptions and perpetuates European divisions of the land. In practice, though, this theme cares more about style, as artists followed or diverged from western models. A few have even helped define Western painting or the United States. The themes do not convincingly display a distinct hybrid culture, but they preserve its roots and tensions.

The Queens Museum adds at least as many stories and artists for its two themes, "Fluid Motions" and "Kingdoms of This World." They stand for the Caribbean as an actual crossroads, for shipping, and as people, with the longstanding spiritual practices that another show called "NeoHooDoo." They are the place of Winslow Homer at his freshest, in the Gulf Stream, and of a Caribbean carnival. One can see them as change and tradition, fluid motion and the flesh, landscape and inscape, rational self-interest and ritual, or this world and the next. They are also familiar and upbeat, with politics for now largely set aside. That missing tension turns up at last at the Studio Museum, with "Land of the Outlaw" and "Shades of History."

Queens tilts toward a weighty, weary twentieth-century realism—and away from deep history. "Fluid Motions" runs to image after image of rowers, fishermen, ferries, and flight. Few have the lightness of Fayad Jamís's 1960 The River, close to Hans Hofmann and abstraction, or the darkness of Alejandro Aróstegui's 1964 The Lake, clotted with pigment and wreckage. Armando Morales Sequeira also has night visions, but of Nicaragua and the Sandinistas, perhaps not unlike Farley Aguilar. Maybe only Janine Antoni, known more for her take on the male gaze, truly gazes at the sea and sky. She walks a tightrope in her native Bahamas, where improvisation and imbalance go well with memories of growing up.

"Kingdoms of This World" shies away from religious visions, in favor of Latin American women and public celebrations. They appear in paint, on video, and in Laura Anderson Barbata's larger than life mannequins. They appear in Coco Fusco's 1993 performance, as a caged member of an imaginary tribe. They seem averse to nightmares, apart from Ariel "Pajarito" Jiménez's 1998 reveler defending himself against a devil in the clouds. They seem averse, too, to introspection, apart from K. Khalfani Ra's 2010 painted face half obscuring and obscured by Bible pages. Amina Gutiérrez's 1986 Homage to Ana Mendieta gives one last look at this world, with a woman lost amid fish, faces, a tenement, and the artist's thick wood frames.

A western past?

From the sound of it, "Counterpoints" should insist on Caribbean responses, as with María Magdalena Campos-Pons on her way from Africa, Firelei Báez on a revolution in Haiti, or Yoan Capote and Zilia Sánchez in Cuba. Instead, El Museo del Barrio finds life under western eyes. Yes, European painters had arrived by 1780, and William Blake illustrated his poem "Little Black Boy." Paul Gauguin dropped by in his search of the primitive. Camille Pissarro was born on the island of St. Thomas and, as a Jew and founding Impressionist, embodied cultural hybrids as well as anyone. Alexander Hamilton, born in the West Indies, looks an emblem of American history, in John Trumbell's portrait.

One can still find snappy counterpoints. In a show light on photography, Leo Matiz in the 1940s documents circus acrobats and Men of Petroleum with a style out of Henri Cartier-Bresson and The Decisive Moment and an ethic of courage and compassion. Felipe Jesús Consalvos adapts collage in 1950, to Uncle Sam Wants Your Surplus Fat. Soon after, Albert Huie uses short brushstrokes and flattened perspective to suggest a Jamaica constructed from its crops. Abel Barroso's elegant cigar boxes, one with a golfer inside, update plantation culture for tourism. Mostly, however, this theme presents the Caribbean as western history.

"Patriot Acts" sounds like a declaration of independence. Instead, it comes off as a textbook in Western art, but from the point of view of the workshop. After the colonial period of "Counterpoints," it begins with the Romantic sublime, as seen by Danes, Germans, and French. (After all, F. E. Church had skipped straight from North to South America.) And then comes pretty much every modern style.

Mostly, artists seem mired in a past marked out for them by others. Those looking for familiar prewar names will find them, like Wilfredo Lam from Cuba or Armando Reverón, with the vines of his native Venezuela. Gego, raised as Gertrude Goldschmidt before leaving Germany for Caracas, pulls things screaming and kicking into abstraction. Those expecting Postmodernism as the embodiment of a hybrid culture will find little of it. Félix González-Torres leaves his leavings, Ana Mendieta celebrates the female body in sand, and Jean-Michel Basquiat stands dutifully for diversity. Yubi Kirindongo sculpts car tires in 1990, like Chakaia Booker but without her plays on abstraction and representation.

The most overt dissent, Jeanette Ehlers's woman trapped amid plantation luxury, is from Denmark. One sees her waltzing, but only in a mirror. The leaden black woman as Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring (from a past great era of Dutch painting) is from the Netherlands. One has recurring motifs of exile and images of women, as with Celeste Woss y Gil's 1940 self-portrait smoking, in the style of Diego Rivera and the Mexican muralists. With May Henriquez in 1952, a woman carved as tree branches seems alternately dancing and struck dumb. With Arlette da Costa Gomez in the 1990s, a woman crouches at the foot of a staircase as in a prison.

Some thrive within a European past. Noé León in 1965 recovers Henri Rousseau for the tropics, while Amelia Peláez's fish on a table has an intensity that late Picasso rarely matched. Hervé Télémaque combines his tribute to Picasso with Che's beret. Another Haitian, Jacques Enguerrand-Gourgue, intends his beast to draw on tribal as well as Cubist magic. For all that, though, one may happily move on to Harlem for more dangerous conflicts. When Hipolito Ocalia finds white teeth, anxiety, and humor in the style of folk art, one remembers that even that category is ultimately a western definition.

Outlaws and icons

"Crossroads of the World" continues at the Studio Museum with everything that the rest of this elephantine survey is not. Those short for time could do worse than to begin and even end here. (Besides, the other two museums allow ten more weeks, should one change one's mind.) Its eighty works, although packed tightly, give its two themes a crisper outline. It has more contemporary art, although not Ebony G. Patterson from Kingston, Jamaica, to question the relationship between origins and impacts, and more room for anger and terror. This is not about meeting points, whether geographical or spiritual, but about savagery and race.

Even then, things are not what they seem. One theme, "Land of the Outlaw," evokes the fears of colonizers and, conversely, the seeds of violence. And sure enough, a Frenchman, Jules Louis Philippe Coignet, painted Europeans caught in an ambush in 1835—while a Haitian, Wilson Bigaud, could evoke a more alluring Murder in the Jungle in 1950. Then again, the bandits, for the most part, are hardly role models in the fight against imperialism. They include Papa Doc Duvalier and gangs in LA. Voodoo and Hollywood notwithstanding, the only zombie is a pathetic Fidel Castro, in Eugenio Merino's 2008 sculpture.

Outlaws can terrify more than invaders, as in Anna Lee Davis's 1989 My Friend Said I Was Too White. They can also include the repressed within native traditions, like René Peña's Cuban male—an index finger in the photograph poised on the tip of a knife blade in place of a prick. They can even offer nurturing, like Thierry Alet's avenging angel, its black silhouette against looser white wings, blue skies, brown shadows, and mysterious text. Its descent could pass for an odd two-step and its butt for a penis. And with dismay comes hope, as with Marisa Jahn's ongoing project, El Bibliobandito. As kids explain on video, "As soon as the cops left, we got right to work making books."

Race is inherently ambiguous, but "Shades of History" sounds more clean cut. At least this second theme starts that way. Prints depict the slave trade from as early as 1791 and, in seeming response from Gerrit Schouten, a diorama from Suriname (also a site for Remy Jungerman). Only the scene is not postmodern but from 1819, by an artist of mixed ancestry who recreated entire villages and slave quarters—their inhabitants, almost, at ease. Who knew? It is a short step to Dudley Irons's 1995 model Black Star Liner, its luxury disturbed by a forward machine gun and the insignia FATE.

"Shades of History" has its share of torments, like the 1966 Seven Brothers by Kapo Mallica Reynolds. However, race as difference also points back to the Haitian revolution, the slave revolt led by Toussaint Louverture. A bust of Napoleon by Antonio Canova dates to 1802, well before Canova's Washington and two year's before Haiti's independence—and the year he undid France's abolition of slavery. Toussaint Louverture turns up at least three times, once by Jacob Lawrence amid prints of toilers, marchers, and riders. Edouard Duval-Carrié's 2003 profile version occupies a circle wreathed in clotted smoke, like a coin that has weathered more than heroism. Other icons of persistence extend from women workers in Panama to Arthur Schomburg of the Harlem Renaissance and to Derrick Walcott, the poet, with a book illustrated by Romare Bearden.

Yet not even icons can ensure the march of progress. A Cuban protester who refused water, drawn by Geandy Pavón in sugar water, vanishes again and again before one's eyes. That coin is pink, while the heroic general has feminine eyes and lips. The museum's presiding deity, Renée Cox's 2004 Redcoat, has its own ambiguous nationality, sexuality, and race—with a sword, crossed arms, and a distinct resemblance to Michael Jackson. David Boxer's carved goddess stands between thrones mounted by skulls, formed of official stamps, like a last record of human traffic. The Caribbean may or may not be "crosswords of the world" or even of the Americas, but its art is still at the crossroads.

"Caribbean: Crossroads of the World" ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem through October 21, 2012, and at El Museo del Barrio and the Queens Museum of Art through January 6, 2013.